The works of Quintus Horatius Flaccus, or Horace, span an extraordinarily wide range, making him one of the central authors in Latin literature. Horace seemed to be just as comfortable writing about love and wine as he was about philosophy and literary criticism. However, the phrase that both best encapsulates Horace’s moral stance and saves him from oblivion, is the phrase ‘carpe diem’ (Odes 1.11.8), which endures well to the modern ages as a slogan on T-shirts and the name of a trendy line of leather goods.

More than a poet, Horace was also a key literary figure in the regime of the Emperor Augustus. Rhetorician Quintilian described Horace’s versatility as being: “… lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words.” This very versatility may have been his saving grace as his career coincided with Rome’s momentous change from a republic to an empire – a change which would have demanded him to maintain a delicate balance between his old republican friends and his association with the new emperor. This earned him praise by some, yet for others he was described as nothing more than: “a well-mannered court slave”.

To investigate Horace’s experience in this delicate period, the poet himself seems to be the most valuable resource. Consistent with his ambiguity, Horace speaks from each genre as an ‘I’ who is both no-one socially, and a member of the inner circle.

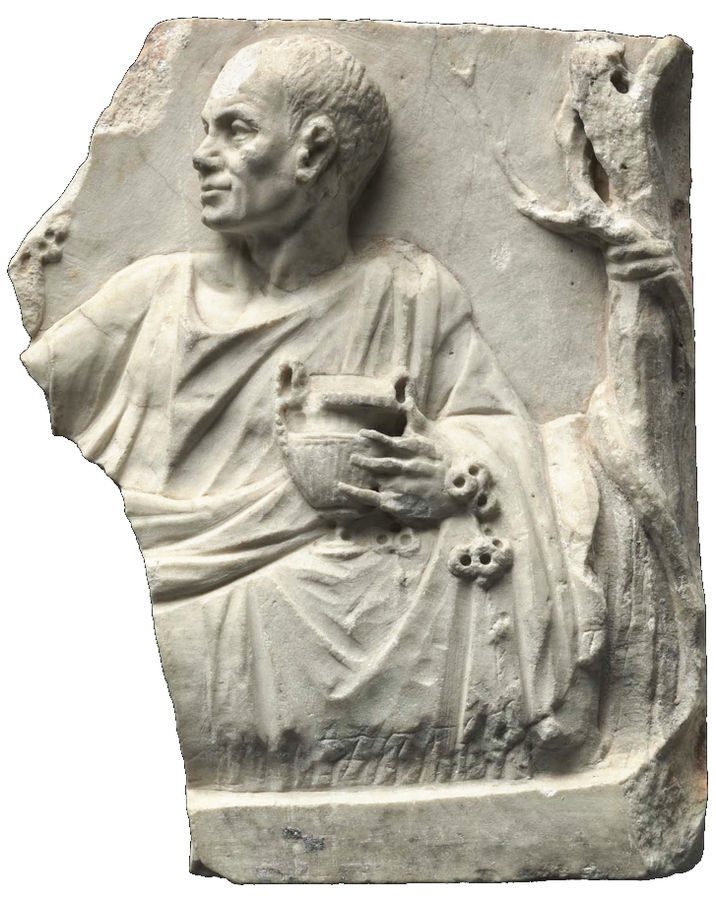

Horace’s father was a slave who gained his freedom before Horace’s birth. He then went on to become an auctioneer’s assistant. He evidently flourished as he was not only able to own a small property, but he could also afford to take his son to Rome and personally ensure that he got the best available education.

So, Horace found himself a student in Athens by 46 BC. Two years later, after the murder of Julius Caesar, Athens came into the possession of his assassins Brutus and Cassius, who clashed with Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar’s great-nephew and appointed heir. Horace joined Brutus’ army and evidently made such an impression that he was appointed Tribunus Militum (Tribune of the Soldiers). To put this in context, a Tribunus Militum is a rank just below the Legatus, which was equivalent to a modern high ranking general officer. As young men of equestrian rank often served as Tribunus Militum as a stepping stone to the Senate, this would have been an exceptional accomplishment for Horace who was a mere freedman’s son.

In the rather peculiar absence of the Legatus, Horace and his fellow tribunes commanded one of Brutus’ and Cassius’ legions at the two battles of Philippi – pitting himself against Antony and Octavian. After their total defeat, Horace fled back to Italy, only to find that his father’s farm at Venusia had been confiscated to provide land for Octavian’s veterans.

Horace then proceeded to Rome. By 39 BC, he had obtained a general amnesty as well as a minor post as one of the clerks of the treasury. A year later, he was introduced to Gaius Maecenas, who later brought him to the notice of the new Roman Emperor Octavian, the man he fought against in Philippi.

The Poet and the Emperor

We may wonder about the change in Horace’s ideals as he was a high-ranking military officer of Brutus and Cassius, before his encounter with Octavian. This question is addressed in his Epodes as the tone reflects his anxious mood after the Battle of Philippi. Horace shows himself sensitive to the tone of political life at the time, the uncertainty of the future before the final encounter between Octavian and Mark Antony, as well as the weariness of the population in the face of continuing violence. The first book of the Satires, which he published in 35 BC, reflects Horace’s commitment to the young emperor’s attempts of restoring traditional morality, defending small landowners from large estates, combating debts and encouraging Novi Homines (New Men) to take their place next to the traditional republican aristocracy.

Another clue of Horace’s change in attitude to align himself with the new regime came after Octavian had defeated Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BC. Horace published his second book of eight Satires in 30 – 29 BC. While in the first Satires, Horace had limited himself to attacking relatively unimportant figures such as businessmen or courtesans, he showed an even less aggressive tone in the second book by criticizing absolutely no one – preferring to delegate the job of critic to others.

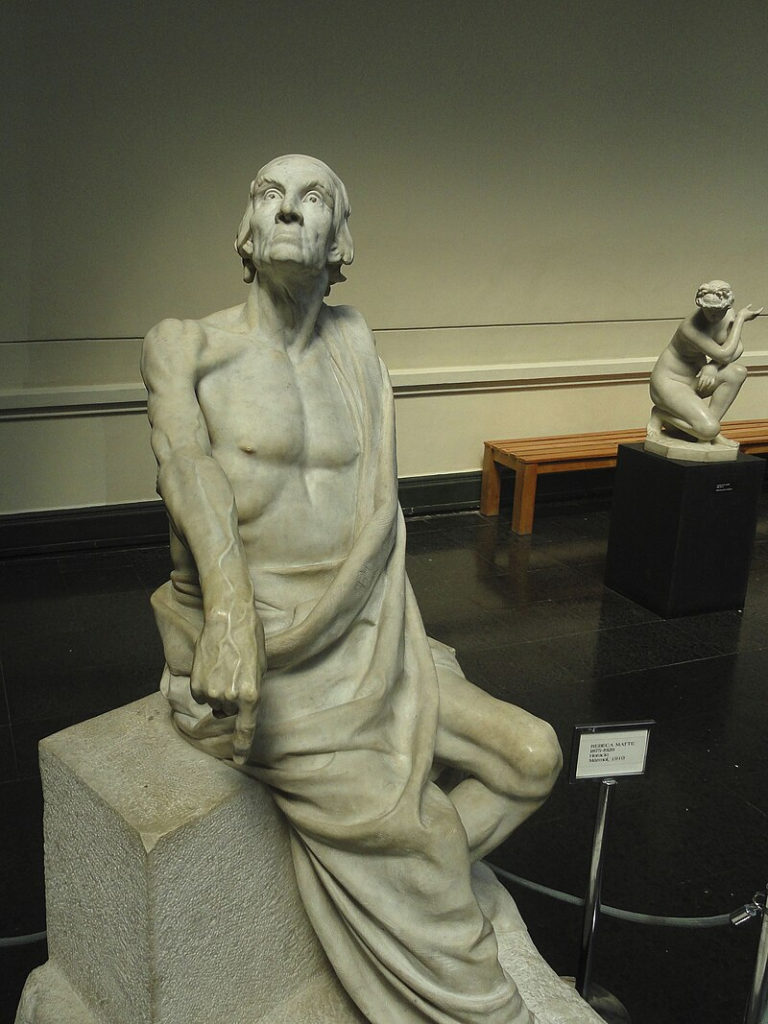

While Octavian, styled Augustus in 27 BC, settled down, Horace published his three books of Odes in 23 BC, where he stayed clear of any talks of political discontentment and described his personal experiences – familiarizing the reader with his everyday world – focusing on the customs of a sophisticated and refined Roman society. This seemed to impress Augustus, as the emperor offered Horace the post of his private secretary. However, maintaining his independence, Horace declined on the plea of ill health. Augustus did not resent his refusal. In fact, the two men seemed to have developed a loyal friendship. Suetonius, a biographer of the 2nd century BC, quotes a letter he received from Augustus, from which it emerges that Horace was ‘short and fat’. Horace himself good-naturedly confirmed his short stature.

By this time Horace was virtually the number one poet in Rome. In 17 BC he composed the ‘Secular Hymn’ for ancient ceremonies, which Augustus had revived to provide a religious sanction for the regime and for his moral reforms of the previous year. Horace was apparently still a loyal friend of Maecenas, the emperor’s adviser as, on his deathbed in 8 BC, Maecenas bid Augustus to: “Remember Horace as you would remember me.” However, Horace himself died a few months later after naming Augustus as his heir.

Have We Been Misunderstanding the Phrase “Carpe Diem”?

If we bear in mind Horace’s enduring relationship with Augustus, together with certain other factors such as the political autocracy of the time and Horace’s own detached and even evasive personality, then it does become possible to deduce from his poetry certain conclusions about his views and his life. To his friends, the men to whom his Odes are addressed, Horace was affectionate and loyal. He was tolerant and mild, but capable of asserting himself when necessary. He was also humane, realistic and, most of all, detached and careful. Would this cautious man really believe in the idea of ‘seizing the day’?

‘carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero’ (‘seize the day, put very little trust in tomorrow’)

The phrase ‘Carpe Diem’ (usually translated as ‘seize the day’) is part of the longer: ‘carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero’, which is translated as: ‘seize the day, put very little trust in tomorrow’. The ode says that, as the future is unforeseen, one should not leave his future to chance. Instead, one should do all one can today to make the future better. Other poets quickly picked up on this – spawning others such as: ‘Collige, virgo, rosas’ (Gather, girl, the roses) by Roman poet Ausonius (310 – 395 AD) which encouraged youth to enjoy life before it is too late. The medieval latin commercium song dating to 1287, ‘De Brevitate Vitae’ (On the Shortness of Life), sang the praises about taking joy in student life, with the knowledge that one will someday die. Also related is the expression: ‘memento mori’ (remember that you are mortal) which carries some of the same connotation as ‘carpe diem’.

For Horace, mindfulness of our own mortality is essential to remind us of the importance of the moment. However, over time the phrase ‘memento mori’ came to be associated with penitence. Today, listeners may interpret the two phrases as representing opposite approaches. ‘Carpe diem’ urges us to savor life and ‘memento mori’ urges us to resist life’s allure. Neither of these captures the original sense of the phrase as intended by Horace. Nevertheless, the phrase ‘carpe diem’ established itself in the centuries-long persistence of Proverbs, Wisdom of Solomon, Hellenistic and Roman lyric poetry, medieval motifs such as ‘Ars Moriendi’ (The Art of Dying), ‘Memento Mori, Memento Temporis’ (Remember the Time), as well as writings by Shakespeare and Ben Jonson. These philosophies provide us with interesting interpretations of ‘carpe diem’ – most of them were consciously, or subconsciously, incorrect. In fact, ‘carpe diem’ may have been the most misquoted Latin tag ever existed with its enduring scandalous mistranslation as ‘seize the day’. The word ‘carpe’ originates from the word ‘carpere’ (to pick), not ‘rapere’ (to rape) or ‘capere’ (to catch) or ‘sumere’ (to take). Therefore, ‘carpe’ did not convey rushed pleasures, but the attempt to slowdown the present – by plucking and grazing.

‘Memento Mori, Memento Temporis’ (Remember the Time)

To ‘pick’ the day, then, one would have been much more cautious in one’s movements, careful to not disturb the animals or pick the wrong fruits. This interpretation would also have been closer to what we knew of Horace as a man – his cautiousness, his sensitivity to his emperor and his readers, as well as his detachment.

We may conclude that, for Horace, time is the part of him that is outside of his full control. Although the new regime of Augustus seemed to be far removed from wars, for Horace who had lost his home and his position, the new state is a warlike empire. He coped with this by controlling the images of war through his poems’ structure, confining them in the outer frame, while dedicating the contents of his writings to pleasure under the rule of Augustus. He picked his battles and distanced himself from any positions that would have placed him at the center of the empire, in order to dedicate his work to letting his readers feel safe – by teaching them to ‘pick’ their own battles.