In modern times, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BC) is remembered as the greatest Roman orator. A prolific thinker, his writings include books on rhetoric, orations, philosophical and political treatises, as well as letters. Although more than 900 of his correspondence between 67 and 43 BC survive, this is only a very small portion of the letters that he wrote and received. Many of his letters did not survive, and many others were, perhaps understandably, suppressed for political reasons after his death.

Four collections of Marcus’ letters survived. The two collections that are considered to be some of the most reliable sources of information for the period leading up to the fall of the Republic are Epistulae ad Familiares (“Letters to Friends”) which is a collection of letters from Marcus to various public and private figures and Epistulae ad Brutum (“Letters to Brutus”), a collection of letters between Marcus and Marcus Junius Brutus, who conspired against Julius Caesar. Then we have two collections which gives us valuable information about Marcus Tullius Cicero as a man navigating his relationships with his nearest and dearest. One of these collections is Epistulae ad Atticum (“Letters to Atticus”), which is a collection of letters from Marcus to his friend Titus Pomponius Atticus. Featuring letters from 68 to 44 BC, this collection provides us with a candid view into Marcus’ character through unfiltered confessions, self-revelations and his day to day moods. But the most personal of his surviving letters is Epistulae ad Quintum Fratrem (“Letters to brother Quintus”), a collection of letters from Marcus to his younger brother Quintus which was written with the freedom and frankness only granted to family never to be found in his correspondence with others.

With Quintus, his younger brother by four years, the famous Marcus Tullius Cicero speaks as he would to a brother, friend, confidant and colleague. Sometimes one would even see traces of brotherly bickering. In one letter Marcus refers several times to a poetic work in progress about Julius Caesar and his campaigns in Britain. In this letter, Marcus also appears to be responding once more to Quintus’ ongoing nagging as to the whereabouts of his promised contributions to Quintus’ poetic work. Marcus’ response to his brother’s nagging is that although he feels capable to write, he lacks the time and inclination. And why does Quintus ask him, Marcus, to contribute something that he, Quintus, is already so good at doing himself? Marcus then goes on to share with his brother some of his current frustration about Roman politics and the paralysing effects it continues to have on him. He then turned back to the subject of literature by answering Quintus’ question about a shipment of books before commenting on Quintus’ recent output of tragedies which was no less than four plays in just sixteen days.

The Brotherly Affection of Marcus and Quintus Tullius Cicero

Marcus and Quintus Tullius Cicero were the sons of a wealthy family in Arpinium. Educated both in Rome and Greece, Marcus completed his military service under Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, the father of the general Pompei the Great. Later, a 27-year-old Marcus’ defence of Sextus Roscius, a citizen farmer from Ameria, against a charge of patricide in 80 BC, established his reputation and helped him start his public career as quaestor in western Sicily in 75 BC.

His brother Quintus was Aedile in 66 BC where he was responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. He then went on to be a Praetor in 62 BC where he acted as the senior magistrate of the city with the power to summon the Senate and to arrange the city’s defence in case of an attack. He later became Propraetor of the Province of Asia for three years 61-59 BC. During the Gallic Wars, he served as a legatus under Julius Caesar and accompanied Caesar on his second expedition to Britain in 54 BC. He again served under his brother Marcus when Marcus became governor in Cilicia in 51 BC. Therefore, although Marcus is the more famous Cicero brother, Quintus was also a competent and prolific author, and no less accomplished in Roman politics than his older brother.

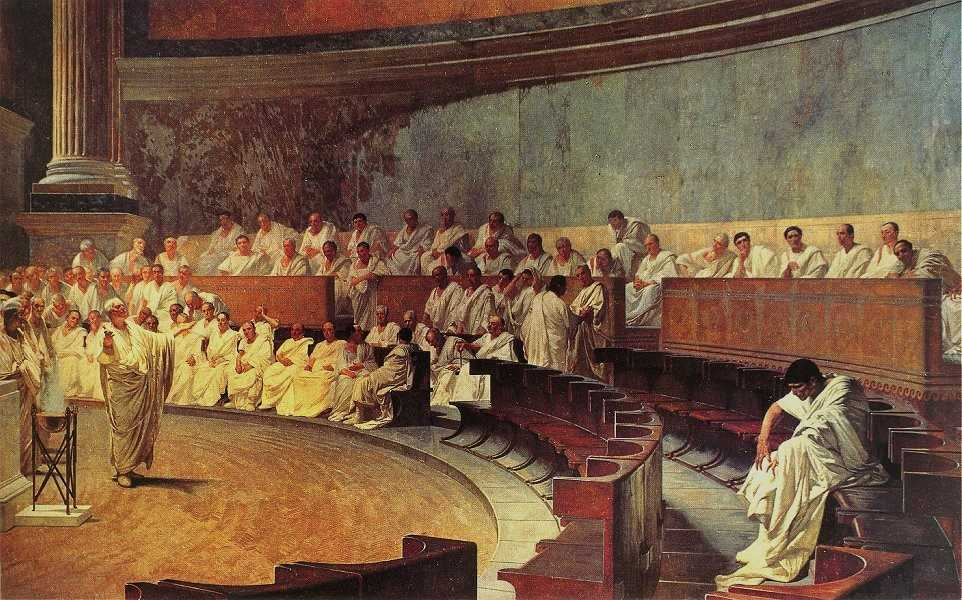

Despite his ambitions and accomplishments, as a Novus Homo (“a New Man”), a man without noble ancestry, Marcus was never accepted by the dominant circle of Optimates (“Best Ones”), the conservative political faction in the late Roman Republic. After 63 BC, Marcus himself attributed his own political misfortunes partly to jealousy and partly to the spineless unconcern of the complacent and out-of-touch Optimates. Despite serving under Pompey’s father early in his career, Marcus never quite achieved the close political association with Pompey the Great that he longed for. A natural politician, Marcus was perhaps more ready than some men to compromise ideals in order to preserve his vision of the republic. However, although he acknowledges in De Republica that the republican government needed the intervention of a powerful person to ensure its stability, he has shown little understanding of its inherent weaknesses.

The brothers seemed to have had not only a close familial relationship, but also a close working relationship where the success of Marcus would also have been the success of Quintus. Although Marcus was thoroughly learned in Greek rhetorical theory and political science, lofty ideas do not win elections. Quintus, with all his achievements, did not seem to be as idealistic as his brother. In fact, Quintus was more impulsive. During military operations, he had regular fits of cruelty which was a quality frowned upon by the Romans of that period. He also had a penchant for old-fashioned and cruel punishments, such as putting a person accused of patricide in a sack and tossing him into the sea. In one of his letters to Atticus, Marcus wrote that he did not dare to leave Quintus alone because he was afraid of what kind of strange ideas Quintus might have.

In 64 BC, when the 42-year-old Marcus ran for consul, the highest office in the republic, Quintus bluntly told him that the other candidates that year were so unappetizing that, with a good campaign, even the dull Marcus actually had a small chance of winning. Quintus then proceeded to write his campaigning advice to his brother in Commentariolum Petitionis, a short handbook on electioneering known as the winning guide for Marcus Tullius Cicero ‘s campaign for consul in 64 BC.

Both in the opening lines and in the last paragraph of the work, Quintus Tullius Cicero speaks to his brother Marcus in a fairly straightforward, fraternal tone and, at the end of the letter, asks him to express his comments, to make supple-mentions, to correct the writing with him, so that it could be published on a later date.

Although we can always debate, and indeed there has been debates, on whether or not Quintus wrote the Commentariolum Petitionis, it is undeniable that the Commentariolum provides formidable knowledge of the events being discussed in it. We can therefore comfortably draw the conclusion that its author must have been a contemporary who experienced these events from quite a close distance. References that are made about Marcus’ situation and background through deliberately unfinished words or sentences implies that the addressee understood what the author meant also gives us the impression that the author would have been someone who was not only very familiar with how the Roman government worked, but also someone with a very close personal relationship with Marcus himself.

Marcus, His Children and Family Tradition

The love of parents for their children was not only one of the ideals of Roman culture but also a natural everyday occurrence. This was also the case with Marcus Tullius Cicero and his children. In his study of children and families in the Ancient Regime (1960), French medievalist and historian of the family and childhood Philippe Arie argued that a proper notion of childhood emerged only in the modern period. However, Australian classical scholar Suzanne Dixon asserts that a more sentimental ideal of Roman family life had already arisen in the Late Republic.

We can see this sentimental familial relationship from Marcus’ relationship with his children, Tullia and Marcus. To define this relationship, English scholar of Ancient Rome Susan Treggiari uses the term “paternal instinct”. However, she defined it as the “defence of hearth, home, fortunes, household gods, wives and children” instead of an emotional attachment relating to a father, such as showing affection, encouragement and so on. Classical scholar Elizabeth Rawson emphasizes how close Cicero was to his daughter who showed greater understanding for him than his wife Terentia while his son Marcus is described as possessing “his mother’s practical outlook and abilities”.

Marcus’ paternal care reveals a radical difference between his daughter and son. In his letters, Marcus utterly ignores his daughter’s education but is very concerned about that of his son’s. However, we would be mistaken to assume that Marcus would ever let Tullia remained uneducated. In an aristocratic household, daughters took part in social events such as invitations to cultivate friendships and advantageous connections, and participated in the conversations usually held on such occasions. In Marcus’ earliest surviving letters to Atticus, written in 68 and 67 BC, the 10-year-old Tullia asks her father to send her regard to Atticus who, she reminds him, has not yet given her the small gift that he had promised her. Tullia’s acquisition of knowledge and social customs comes from her day to day interactions in an environment where Roman poets and Greek intellectuals moved freely. The everyday communication about philosophy, literature, and politics in the aristocratic homes would have also contributed to her education. Tullia would also have had access to Marcus’ library, and we can assume that she would be free to discuss books with her father when he was available. Marcus looked upon his daughter as an educated woman as, not only does she write her own letters, she also reads the letters addressed to him over his shoulder and shares her assessment of the critical political situation of 49 BC with him. However, the education she receives at home prior to her first marriage, that is when she was between the age of 13 and 16, seems to have been so self-evident that it goes almost unnoticed in Marcus’ letters as if her achievements and education was to be expected for a young lady of her class. In contrast, Marcus’ correspondence contains many detailed references to his son’s education. In a letter to Atticus written in April 59, Marcus conveys his then 6-year-old son’s request to “give Aristodemus the same answer about him as you gave about his cousin, your nephew”. Aristodemus, referred to only once in Marcus’ letters, was likely the boys’ private tutor, and that they were obliged to send their apologies for missing a grammar lesson.

Marcus’ paternal endeavour to oversee his son’s progress is also evident in one of the letters written to his brother, Quintus, which establishes clearly that Marcus was actively involved in the education of both his son and nephew, Quintus’ son. In 54 BC, should Quintus raise no objections, Marcus told his brother that would tutor his nephew himself as he had now gained quite some practice through teaching his own son during his enforced political inactivity. Thereupon, his brother Quintus writes to his son, also named Quintus, instructing him to now regard his uncle as his tutor. Marcus informs his brother that he will introduce his nephew Quintus to the declamation exercises himself. Another important tutor for both the younger Marcus and Quintus was Dionysius, a freedman of Atticus. In July 54, Marcus writes to Atticus, requesting his earliest possible visit so that Dionysus could teach both him and his son. Three years later, Dionysius is in fact present in Marcus’ household, who commends him in his letters to Atticus. Although Marcus remarks that the two boys complain about Dionysius’ fits of temper, Marcus defends the tutor. However, two years later, in 49, Marcus describes this once highly reputable tutor as lacking the Graeco-Roman blending of educational ideals among the Roman elite and that he would therefore rather teach his son and his nephew himself. In a letter to Atticus written two days later, Marcus reports his dismissal of Dionysius. This suggests that the elder Marcus was intensely concerned with his son’s progress and tutoring, just as he was as a patruus (a paternal uncle) with his nephew’s, and this concern for better or worse involved strict supervision.

Various letters concerning the younger Marcus’ study visits to Athens in 45 and 44 attest to his father’s surveillance. On the one hand, young Marcus writes his father letters that demonstrate that his writing style and knowledge of literature were progressing. His father was evidently happy with this as, in two letters to Atticus, he praises his son’s letters as being written “in a good archaic style indeed and pretty long”. However, the dedicated father is not content to let the matter rest there. In several letters to Atticus written in the spring of 44, Marcus expresses his intention to travel to Athens to observe his son’s progress for himself. When this intention never materialized, instead of personally inspecting his son’s progress, Marcus commissioned various tutors, including Leonidas and Herodes, to send regular progress reports.

In a letter to Tiro, the elder Marcus’ secretary, from the summer of 44, young Marcus observes that that his humanissimus et carissimus pater (“kindest and dearest father”) had dismissed Gorgias, his teacher of rhetoric. While Marcus found the Gorgias’ lessons to useful, he realizes that he would have been “taking a lot upon myself in judging my father’s judgement”. These references to a notion of education that differs from modern educational goals. In ancient Rome, sons were not meant to develop their individual abilities and interests, instead lessons were aimed at imparting skills designed to enable male children to further pursue the social and political prestige already established by their fathers. The purpose of paternal control, therefore, was to maintain a certain social standing for male offspring and to safeguard the family name. Cicero’s funding of Marcus’ education reveals this intention. In his letters to Atticus, he often asks about the safe receipt of money that he sent for his son. He also frequently requests that Marcus be well endowed which indicates his concern about his son possessing sufficient disposable assets to afford a lifestyle that commensurate with his status as a matter of safeguarding his father’s social standing and dignity apart from his father’s parental duty towards him.

Various other aspects of the education of Young Marcus and his cousin Quintus illustrate how the the older Cicero brothers sought to establish a joint family tradition. Marcus informs his brother that he will teach his son and his nephew additional lessons, asserting that his own rhetorical training is more learned and more abstract than their current tutor. He therefore intends to introduce their sons to a declamatory technique that both fathers learned in their youth. This rather simple comment allows us to explore how family identity was established in Roman culture. Whereas existing aristocratic families may be modelled on a more or less long line of ancestors chosen on the basis of their success, enabling the descendants to follow in their footsteps, the Cicero family had to develop a link with a “glorious” past before doing anything of the sort. One part of this initiative is Marcus’ active participation in the education of his son and nephew. Thus, he assumes the role of both pater and patruus severus. Young Marcus’ letter to Tiro gives us a glimpse of the Roman notion of severitas, which is that even at the age of 20, young Marcus will never dream of challenging his father’s decision. Obviously, the bond between father and son was such a central part of Roman culture that the responsibility of a son to practice pietas and proper reverence for his father’s will made open criticism inconceivable.

The Marital Career of Tullia

In an aristocratic household, a son’s cursus honorum corresponded to a daughter’s marital career. In a culture in which her father’s and her husband’s positions in society determined a woman’s way of life and social standing, marriage represented a crucial decision for daughters. In the 1970s and 1980s, women’s studies criticized the fact that women served only to secure relationships between men, thus having their personal interests ignored. However, our modern concept is very different from Tullia’s and Terentia’s perception of their own places in society. While a Roman father by all means utilized his daughter by marrying her off to political allies, and thereafter dissolved the marriage depending upon political and financial developments to then remarry her to someone more advantageous, sons were utilized in exactly the same fashion.

Tullia’s first engagement was to C. Calpurnius Piso Frugi in 67 BC. In his letters referring to his daughter and her prospects, Marcus uses the diminutive Tulliola, giving the impression of his daughter being very young at the time of her engagement. In fact, Tullia was aged between 9 and 12 years old. Her fiance, aged about ten years older, was the son of a praetor and descended from a consular family with whom Marcus have friendly political relationship. Although there are no records of the exact date of the marriage, Marcus refers to Piso as gener in his fourth Catiline Oration in 63 – a designation which could apply not only to an actual son-in-law, but in a broader sense to a man only engaged to be married to his daughter. Calpurnius Piso was appointed quaestor in 58, and died either while holding office or shortly thereafter, making Tullia a widow when she was about 20. Tullia’s next marriage negotiation started in 56 when she was engaged to Furius Crassipes, a rich patrician who attained the quaestorship in 51. Although no records survived on their marriage or subsequent divorce, Marcus was already looking for a new husband for Tullia in 51 BC.

Marcus’ love for his children focuses not on specific behaviour or abilities but instead on their highest possible conformity with those aristocratic values that he expects every vir bonus to possess, and for which he commends both his children and his friends. Notwithstanding that his esteem for his children has nothing to do with their individual personality but instead with conforming to overarching social norms and values, we need not refute claims to Cicero’s “paternal love”. His esteem, however, allows us to recognize the historical and cultural contingency of this particular love. Cicero expresses his love for his children, since this corresponds to the requirements and the moral standards which he expects from the boni and which serve as a standard with which he measures his own life. For it is precisely this yardstick that determines whether a name will find the approval of the senatorial aristocracy in Rome or not.

REFERENCES

Burriss, E. E., (1924) Cicero’s Religious Unbelief, The Classical Weekly, Vol. 17, No. 13, pp. 101-103

Dacre Balsdon, J. P. V., (2020) https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cicero

Dasen, V., Spath, T., (2010) “Cicero, Tullia, and Marcus: Gender-Specific Concerns for Family Tradition?”, Children, Memory, and Family Identity in Roman Culture, Oxford University Press, pp. 147-157

Hendrickson, G. L., (1892) On the Authenticity of the Commentariolum Petitionis of Quintus Cicero, The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 200-212

Kruschwitz, P., (2014) Gallic War Songs (II): Marcus Cicero, Quintus Cicero, and Caesar’s Invasion of Britain, De Gruyter, Philologus, 158(2), pp. 275–305

Litchfield, H. W., (1913) Cicero’s Judgment on Lucretius, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 24, pp. 147-159

Notari, T., (2010) On Quintus Tullius Cicero’s Commentariolum petitionis, ACTA JURIDICA HUNGARICA 51, No 1, pp. 35–53

Sihler, E. G., (1897) Lucretius and Cicero. Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 28, pp. 42-54