In 29 AD, Livia, the Empress of Rome and the widow of Emperor Augustus, died at the age of eighty-six. Although she was the mother of Tiberius, the current emperor of Rome, and an empress through her own marriage to Augustus, her funeral was very low-key by the standards of the Roman imperial family. When Augustus’ sister Octavia died in 11 BC, her funeral oration was delivered by Augustus himself in his capacity as both Octavia’s brother and Emperor of Rome. Drusus, Livia’s younger son, then spoke from the rostra in the forum. Drusus and Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, Octavia’s sons-in-law, then carried Octavia’s remains in procession to her final resting place in the Temple of Divus Julius.

By contrast, the only person who spoke at Livia’s funeral was her great-grandson Caligula before Livia was buried in the Mausoleum of Augustus with minimal ceremony. Tiberius did not speak at Livia’s funeral. He did not release any coins to commemorate her passing and he refused any public honors that the senate wanted to bestow upon her. As a testament to Livia’s influence in her lifetime, though, the senators mandated that the women observe an official year-long period of mourning in which they were instructed to wear black attire, loosen their hair, and not wear any jewelry during this time. The senate also voted for an arch to honor Livia in remembrance of her deeds of charity and goodwill. However, the plan never came to fruition as, although Tiberius did not immediately resist this plan, he instead promised rather heroically to build the arch with his own money instead of using the public funds. However, he conveniently neglected from ever making a start on the arch and thus the senatorial edict was politely disregarded by the emperor.

Perhaps of all the honors that the senate wanted to give Livia, the motion to vote on Livia’s divine honors was the most important. Although Livia’s cult had grown throughout the empire even during her lifetime, the senate’s proposal entailed the formal acknowledgment of her divinity in Rome, complete with a temple and priests of her own. Thus, Livia would have been the first woman in Rome’s history to be dedicated to the worship of a goddess.

Despite his persona as a learned eccentric, Emperor Claudius seized power with efficiency through a military takeover. Therefore, he would have been eager to highlight his family’s prominence to show his credibility. Improving Livia’s standing, as she is his grandmother, would inevitably result in improving his own. Among his first actions were the divine honors bestowed to Livia on the anniversary of her marriage to Augustus as well as what would have been her one-hundredth birthday.

Livia was still held in high regard during Nero’s reign, and she was still highly regarded after the Julio-Claudian dynasty ended in 68 AD. Recognizing the propaganda potential of her likeness, Galba produced multiple coin series in her tribute. An inscription from an unidentified colony, possibly Trebula, dating to 108 AD, reveals that her birthday was still celebrated back then – almost one hundred years after her death. At Pergamum, an ancient Greek city in Mysia, about sixteen miles away from the Aegean Sea, Livia’s and Augustus’ birthdays continued to be observed under Trajan’s reign with festivities that lasted for three days in their honors.

The Good and Bad Apples: Livia’s Ancestry

Some renowned ancient Roman families, like the Julii or the Cornelii, managed to maintain a firm hold on the important positions for so many generations that it became almost like a birthright. Livia was a good example of this system as, on her father’s side, she was descended by blood from the Caudii, one of the most illustrious and successful of all the great Roman houses. The Claudii were prosperous immigrants, and their connection to Rome may be traced back to the migration of the Sabine Attus Clausus and his family to Rome in 503 BC. Attus became the first Claudian consul only a couple of years later, in 495. His successors then went on to hold a consulship in every generation. Generations of the Claudii eventually held twenty-eight consulships, five dictatorships, seven censorships, six victories, and two ovations.

Another one of Livia’s ancestors, Appius Claudius, played a crucial role in the creation of Rome’s first written law code in 451. Another ancestor by the name of Appius Claudius Caecus (340 – 273 BC) was responsible for the creation of the Claudian Aqueduct and the Appian Way and the Claudian Aqueduct. He then went on to become one of the most illustrious men of the old Republic, being revered and consulted as an elder statesman though he was blind and elderly. In a speech he gave before the Roman Senate in 280 BC, Appius Claudius Caecus convinced his fellow senators to reject the peace conditions that King Pyrrhus had given as being dishonorable. This speech has been passed down through the ages and is still used as a textbook when Livia herself was born.

Roman Senator Appius Claudius Caudex was one of the two consuls in 264 BC. When the First Punic War broke out that year, he led the Roman soldiers into Sicily. In the Second Punic War, Hasdrubal was vanquished by Gaius Claudius Nero in 207 as he traveled to join his brother Hannibal.

Prominent Roman families frequently consisted of multiple branches. The Claudii Nerones and the Claudii Pulchri, the two principal divisions of the aristocratic Claudians, were founded by Appius Claudius Caecus’ two sons, Tiberius Claudius Nero and Publius Claudius Pulcher. Livia claim descent from one branch and would later marry into the other. Before Livia’s son Tiberius was chosen be consul in 13 BC, Tiberius Claudius Nero served as the final Neronian consul in 202. The Pulchri experienced constant growth and established themselves as a dominant force in Roman politics.

Despite their roles in ancient Rome, the Claudii are known to be full of eccentrics. Suetonius describes them as violent and arrogant, Tacitus describes their descendants as marked by the old inborn arrogance of the Claudian family and Livy describes the family as excessively haughty and cruel towards the plebeians.

During his consulship in 143, Appius Claudius Pulcher, provoked the Salassi of Gaul into an expensive war in which he lost five thousand troops and was soundly defeated. During a subsequent battle, he evened the odds by eliminating 5,000 people from the opposition. Due to this, he believed that he was entitled to a triumph – a procession through Rome granted to triumphant generals who met certain requirements. When the senate denied his request for funds to stage this triumph, he went ahead and paid for his own triumph staging.

The Claudian ladies were just as conceited as the men. Claudia, the sister of Claudius Pulcher, and the daughter of Appius Claudius Caecus became enraged and openly prayed for her deceased brother to resurrect so that she could ask him to murder another army as a throng of Roman people blocked her carriage. This raging Claudia was a Vestal Virgin. In Livia’s early years, she was still living with the most notorious Claudian woman in history, Clodia Metelli who was well-known for her political influence and wastefulness.

Parents of the Empress of Rome

Alfidia, Livia’s mother, was of far less famous descent. However, her family’s fortune may have drawn the attention of an eligible aristocrat such as Marcus Livius Drusus, as she was the daughter of Marcus Alfidius, a man with municipal rather than senatorial connections. Her origins appear to have been at Fundi, a charming village on the Appian Way in the coastal region of Latium close to the border with Campania. Although Fundi was known for its excellent wine, most Romans saw it as a cheap get-away place as many of them owned rural villas nearby.

Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus, Livia’s father, was adopted into the Livian family despite being born a Claudii. He adopted the nomen of the adopting gens, the Livii, in the manner of the Romans, and added the adjectival form of his original gens, the Claudii, as it was expected of him to take on the praenomen of his adoptive father after adoption; the fact that he was a Marcus and that there was no other well-known Livian outside the renowned tribune Drusus indicates that this Drusus might have been the praenomen of his adoptive father. Livia also got her tribune connection, which gave her the name Drusilla. Her family was also given the name Drusus as a result, and some of her successors chose to adopt it as a praenomen.

If he had become the tribune’s adoptive son, Marcus would have been in a good position. He might have received all or part of his new father’s estate upon his death as Marcus Livius Drusus was dubbed the richest man in Rome by Diodorus Siculus, and it appears that additional accounts corroborate his claim. Furthermore, money from Marcus’s wife’s family may have increased his inherited riches as a large dowry would have been seen by the Alfidii as a small price to pay for an alliance with a socially famous Roman. At a time of intense political unrest in 59 BC, Livia’s father makes his historical debut in Rome.

Upon his return from Spain in 60 BC, Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus came together and established what we know as the First Triumvirate. To finalize the deal, Pompey wed Julia, the daughter of Caesar. Marcus, Livia’s father, a keen opportunist, hitched his wagon to the triumvirate and was despatched on a fund-raising journey to Alexandria in 59 BC, and in around 59 BC, he became a parent when his daughter Livia was born.

Tiberius Nero and Octavian: The Past and Future Husbands

Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 BC as a result of a plot headed by Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius. After this significant event in Roman history, Livia’s first marriage also occurred at a significant time in her life. Tiberius Claudius Nero, her husband, was a member of the less prominent Claudian aristocratic family. His family’s most recent consulship ended in 202 BC.

Tiberius Nero’s father was also a Tiberius. The elder Tiberius Nero led Pompey’s legate against the pirates in 67 BC, controlling the Straits of Gibraltar. In 63 BC, he spoke out against the execution of Catiline’s accomplices without a trial when Cicero revealed they were involved in a significant conspiracy. There is little question that Livia and her husband were linked because of their family names although is uncertain how closely they were related.

In 54 BC, Tiberius Nero entered public life. Aulus Gabinius, a follower of Pompeius, returned from Syria in that year, following a governorship characterized by widespread bribery and apparent incompetence in administration. Once Cicero attacked Gabinius, he became the year’s biggest celebrity, harassed by a succession of ostentatious trials. Tiberius Nero faced competition from Gaius Memmius and Mark Antony for the prominent position of prosecutor before Cicero’s trial for extortion. Tiberius Nero lost the competition.

As a result of his loss of the position of prosecutor, Tiberius Nero was branded as a failure. He traveled to Asia in the late 51 or early 50, seeing some of his clients there. It was during Cicero’s tenure as governor of Cilicia that he visited him. Tiberius Nero appears to have left a lasting impression on his host because of his opposition to the power bloc led by Caesar, Pompey and Crassus. Cicero had given his approval as a possible prosecutor in the Gabinius case. However, before this could come about, Tiberius Nero took the position of Julius Caesar’s quaestor and took command of the fleet in Alexandria, demonstrating his support for the leader. In exchange for his efforts, Caesar granted him a senior priesthood and, in 46 BC, the authority to establish colonies in Narbonese Gaul, including Arelate and Narbo, at Caesar’s command.

The assassination of Julius Caesar and the Ides of March in 44 BC altered his fate and Tiberius Nero had to decide on his profession. But first, he married Livia who was fifteen or sixteen years old at the time as Tiberius Nero was probably in his late thirties. The average age at which women got married at this time seems to have been in their late teens, but in upper-class households, getting married at fifteen was probably the standard, and in aristocratic circles, getting married even earlier was frequent when there was a political benefit to the union.

Caesar’s death created a void that two men fought to fill. Mark Antony was one. The other was Octavian, his great-nephew, who was designated in his will as his heir and adoptive son. He was the man who would change the course of Roman history and end up marrying Livia.

Two days’ trip south of Rome is the Volscian village of Velitrae, the birthplace of the Octavii. Octavian’s father, Gaius Octavius, was a wealthy banker and belonged to the enterprising middle class that made up the so-called “equestrian order.” Octavian was the first member of his family to advance from that class into the Senate.

Caesar sent Octavian to Apollonia on the Macedonian coast to finish his schooling before the year ended. Octavius had been at Apollonia for a few months when his mother sent a messenger bearing the shocking information that Caesar had been killed. He made the quick decision to head back to Italy with Marcus Agrippa and a few other acquaintances.

Through letters from his mother and stepfather, he discovered that he was adopted as Caesar’s son and had acquired most of Caesar’s inheritance. His family, sensing the political uproar that the adoption would cause, counseled him to turn down the adoption. He went to Rome instead of taking their advice. He now adopted the Roman practice of taking the name of the adoptive parent and appending a form of the original gens to it, naming himself Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus.

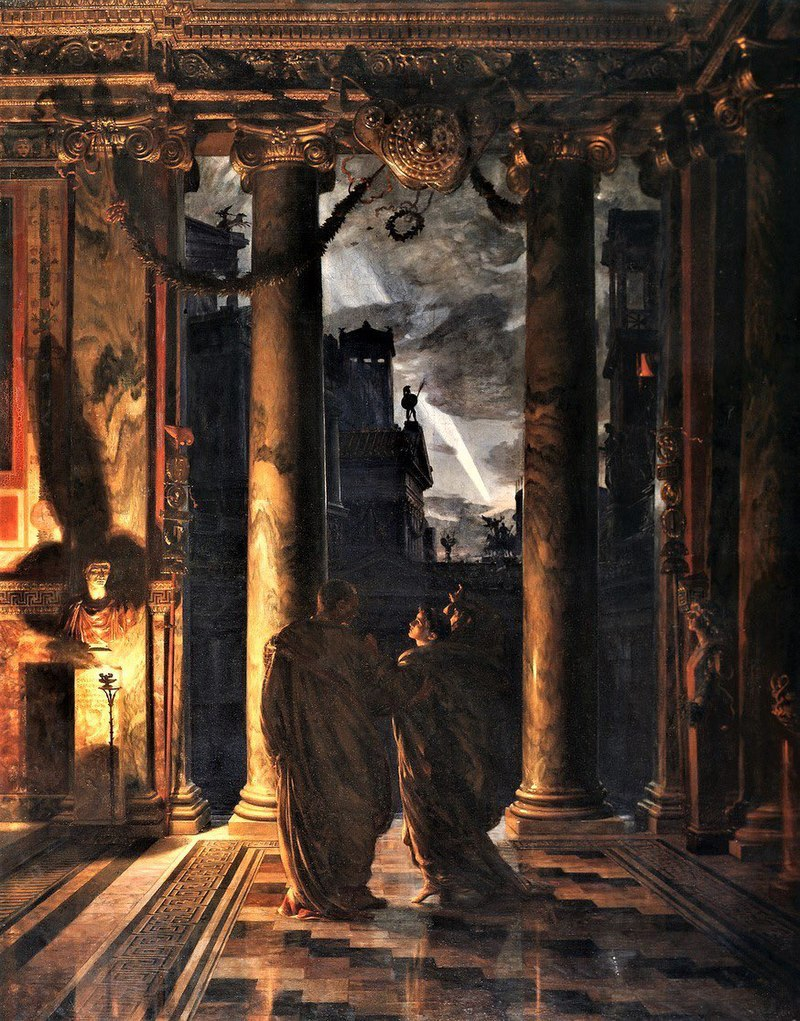

The subsequent years did, in a sense, validate his parents’ misgivings since Octavian and Antony, despite forming the second Triumvirate with Marcus Lepidus, clashed over their desire to succeed Caesar. Compared to its predecessor, the second Triumvirate was more official and granted the trio nearly total authority for five years. It allowed them to destroy all their rivals, even Cicero, and to fight the despots Brutus and Cassius, who were ultimately vanquished and forced to commit suicide at Philippi in Thrace. Like in any civil war, the struggle between Roman political and military leaders in the final century of the republic inevitably engulfed the rest of the populace. Tragic events also entered Livia’s life as a result.

Nothing specific is known about her father’s position during the conflicts between Caesar and Pompey or throughout Caesar’s ascent, but after Caesar’s death, Marcus becomes a supporter of the despots. He is identified as one of the supporters of a senatorial proclamation in 43 BC that assigns Decimus Brutus, the assassin, command of two legions. The triumvirs had banned him by the end of that year. He ran away to the east and met up with Cassius and Brutus, sharing in their loss at Philippi. Although Marcus lived, he is said to have died a brave death later on as, refusing to beg for forgiveness, he committed suicide in his tent.

It was now obvious that Marc Antony and Octavian were at war, and Tiberius Nero chose to support Antony. Tiberius Nero also refused to resign from office after his term and continued to hold the position for longer than was required by law. He was elected to the praetorship in 42 BC.

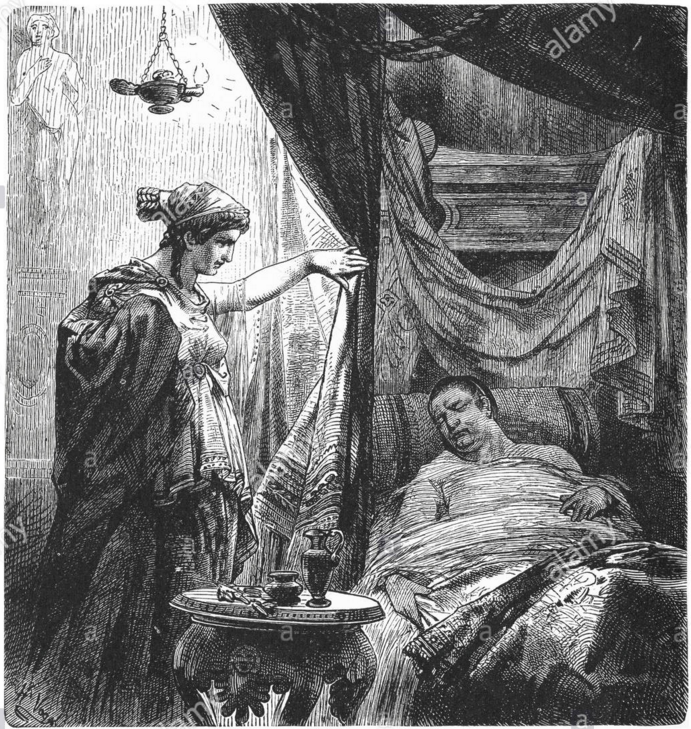

Livia became pregnant early in the same year. Stories have it that she was determined to have a son and employed a technique popular at the time for figuring out the sex of the baby. She took an egg from under a hen that was brooding and warmed it against her breast. To avoid breaking the warmth, she slipped it to her nurse beneath the ruffles of their dresses whenever she had to give it up. A finely crested cock hatched, a sign of a boisterous offspring. Tiberius, the first of her two boys, was born on the Palatine in Rome on November 16, 42. Suetonius documents the year and date as well as the place in Rome, where it is safe to presume that Tiberius Claudius Nero had real estate on the opulent Palatine Hill.

Following their victorious war at Philippi against Caesar’s murderers, the triumvirs had decided on their respective spheres of influence. Marcus Lepidus could only go to Africa. After capturing the East, Antony began his battle against the Parthians. His mission was to put Italy back in order and to keep an eye on Sextus Pompeius, Pompey’s younger son, who had established a haven for fugitives fleeing the triumvirs in Sicily and positioned himself with a sizable fleet.

Octavian took on the menial duty of seizing land in Italy for the retiring warriors. When Antony’s brother Lucius Antonius, and Antony’s wife, Fulvia, became the champions of the dispossessed Italians and sought to stir an uprising against Octavian, Tiberius Nero joined the campaign, and Livia and her son followed him to Perusia, the primary center of opposition.

Following the fall of Perusia in the early 40s, Tiberius Nero fled with his family, first to Praeneste and then to Naples, where he attempted to lead a slave insurrection. He and his family ventured out into the rural wilderness, eschewing the usual paths to travel covertly to a ship. Little Tiberius began to cry during the trip. Fear spread that he might reveal their position. Livia took him from the nurse and, when he refused to calm down, one of her supporters grabbed him from her, seemingly saving the day. In one of life’s great ironies, Livia is running away from the man she would later marry, holding a son who would eventually succeed him.