As it is intertwined with the development of mythologies, storytelling predates writing. The earliest forms of storytelling were usually oral, with gestures and expressions thrown in for good measure. The story was then told using a combination of oral narrative, music, rock art, and dance, all of which contribute to human understanding and meaning through the remembrance and enactment of stories. Prose, poetry, song, dance, and theatrical performances are all ways to tell a story. Archaeological evidence of the presence of stories has been discovered at the Indus Valley civilization site of Lothal in India. The artist depicts birds with fish in their beaks resting in a tree on one large vessel while a fox-like animal stands below. This scene is similar to a story from the Panchatantra of The Fox and the Crow. The Panchatantra is an ancient Indian collection of animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose. Although the surviving work is dated to around 200 BC – 300 AD, it was based on older oral tradition. The story of the thirsty crow and deer is depicted on a miniature jar, with the deer unable to drink from the jar’s narrow mouth, while the crow succeeded by dropping stones into the jar. The animals’ features are distinct and graceful.

However, oral storytelling continued to be an irreplaceable tradition as it is a particularly ancient and personal tradition shared by the storyteller and their audience. The storyteller and the audience are usually physically close, sometimes sitting in a circle. Through the communal experience of storytelling, a personal bond is formed between the storyteller and their audience, and even between one audience member to another. The flexibility of the art of oral storytelling itself, which allows the tale to be shaped and moulded according to the needs of the audience and the environment of the event, deepens this sense of intimacy and connection. The listeners would have also appreciated being present while a creative process unfolded in front of them in real time, as well as the sense of empowerment that comes from being a part of that creative process.

The storyteller, in turn, would have had to be adaptable. They would have had to incorporate their own personality into the story or may have chosen to include additional characters to make their stories more interesting or relatable. To achieve this, they may have had to change their speech from one character to another or moved in a specific way to depict a scene. As a result, depending on the creative strategies or devices that they choose to employ, there would have been numerous variations of a single story coming from one person. We can see an example of the ancient world’s illustration on the value that they placed on storytelling from the 9th century fictional storyteller Scheherazade of One Thousand and One Nights who saves herself from execution by telling stories every night. In India, hundreds of years before Scheherazade, Vyasa reflects on the sacredness of the power of storytelling at the beginning of the Indian epic Mahabharata. “If you listen carefully,” Vyasa says, “you’ll end up being someone else.”

In the Middle Ages, storytellers were included within the definition of minstrels (“little servant”) and were honored as members of royal courts. In the 11th – 12th centuries, the title of minstrel was given to a wide range of entertainers such as singers, musicians, jugglers, jesters and storytellers. Both men and women were employed as minstrels, and a female jester named Adeline was recorded as owning land in Hampshire in 1086. However, high expectations came with this honor. Medieval storytellers were expected to know all the current tales, be well informed on court scandal, understand the healing power of herbs, be able to compose verses for a lord or lady at a moment’s notice, and to competently play at least two of the instruments popular at court at the time. Among the many storytellers in the court of King Edward I (1239 – 1307) were two women named Matill Makejoye and Pearl in the Egg.

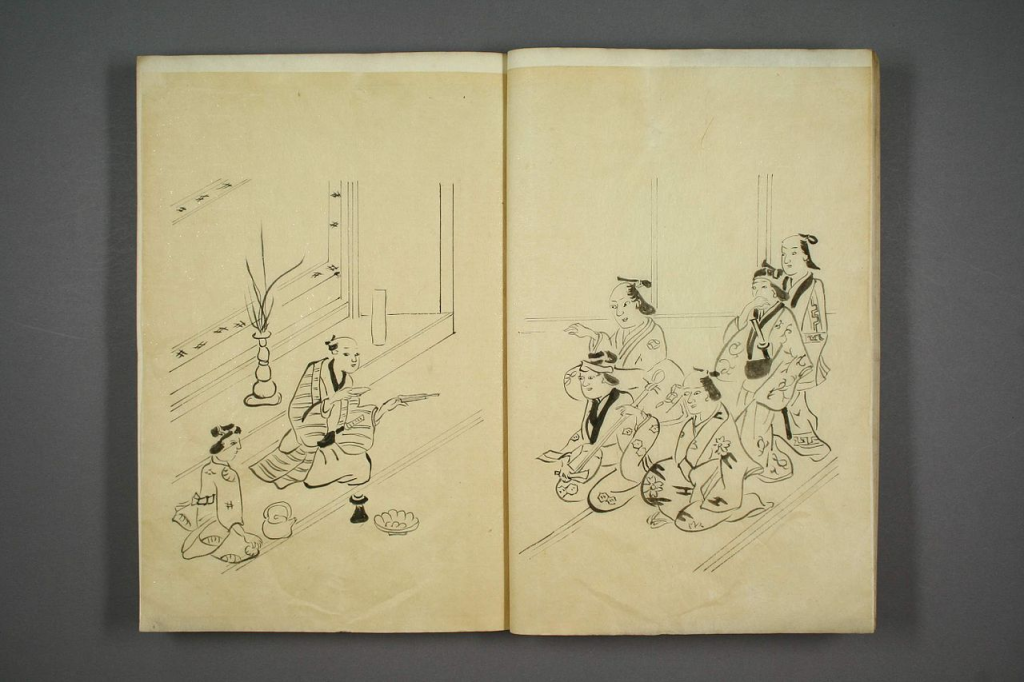

The high expectations put upon the storyteller did not restrict itself to the west. In China, Pingshu demands years of training and a lengthy apprenticeship with a master. Not only must the storytellers memorize extremely long passages, they must also be knowledgeable and well-educated enough to be able to incorporate the origins of certain customs, character backgrounds, history and geography, as well as other enthralling facts about the stories they tell. The pingshu performer is dressed in a gown and sits behind a table, holding a folded fan in one hand and a gavel in the other. The gavel is used as a prop to strike the table to warn the audience to be quiet. The gavel is also used for a variety of purposes such as a way of attracting attention or amplifying the effect of the performance, particularly at the start or at intervals.

In ancient China, storytelling and comic performances were popular, not only among common people but also in noble palaces and mansions. Many old and new stories were created during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), some of which were based on Buddhist scriptures and some of which were accompanied by folk songs. The prosperity of trade and the growth of cities and urban populations accelerated the development of the art form and flourishing of storytelling during the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 AD).

The Laughing Monks, the Talking Horse and the Traditional Japanese Art of Storytelling

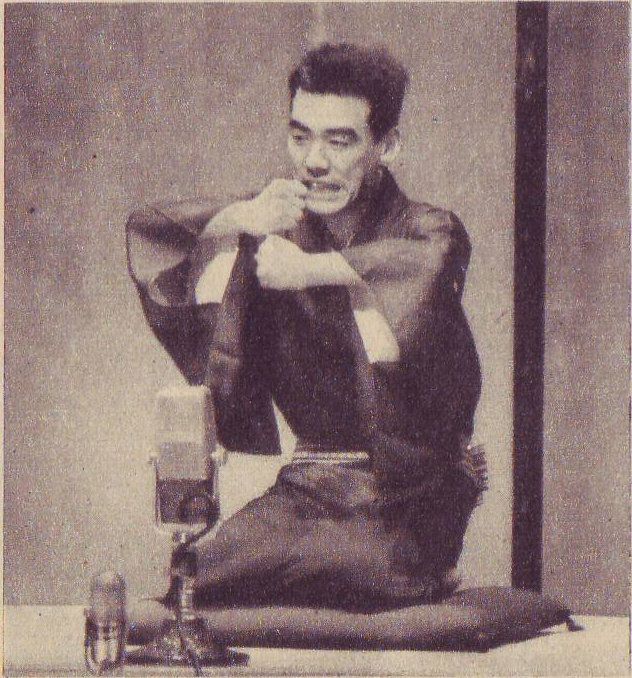

In Japan, a form of entertainment named rakugo emerged during the Edo Period (1603–1868). rakugo (“fallen words”), is the art of comedic storytelling performed by a lone storyteller (known as rakugoka) dressed in kimono. On stage, the rakugoka would sit in the traditional seiza position on a cushion. He would then tell a long traditional story using only a single paper fan and a small cloth or hand towel as props, generally based on tales of farcical comedy or warmhearted human drama incorporating typical characters one would see in their daily interactions. For a very long time, rakugo was something that was only done by men. It was only in 1993 that a woman could also become rakugoka. The story itself would be made up of various characters, all of whom are played by the rakugoka’s voice, which varies in tone, pitch, and volume, as well as slight turns of the storyteller’s head.

Somewhat similar to its older Chinese counterpart, rakugo may have begun as a form of proselytising in the tenth century AD when Buddhist monks began to spice up their sermons by talking to people in a more informal and entertaining manner. They increasingly told humorous stories based on Buddhist scriptures in order to attract a larger audience. These storytelling monks gave birth to the Japanese version of the jester named taikomochi (“drum bearer”). In the 13th century, taikomochi, who originated in the Ji sect of Pure Land Buddhism, became attendants to the daimyo (feudal lords). These attendants were then known as doboshu (“comrades”) because they did much more than just attending to and entertaining their lords – they also served as advisors, artists and tea ceremony connoisseurs. By the 16th century, they had evolved into intellectuals known as otogishu or hanashishu (“story tellers”), in which they narrowed their focus further into humorous storytelling and conversations while also serving as sounding boards for military strategies and reporting to him on buhenbanashi (anecdotes about samurai’s life) or the situation of various districts. They would even fight alongside their lord when required. Due to this demanding job description, during the Sengoku (“Warring States”) period, the post of otogishu were mostly filled by Buddhist priests, chief retainers who retired and withdrew to the sidelines, a fallen daimyo or busho.

After the turbulent age of Sengoku passed, the role of comforting the lord’s boredom was emphasized once more, and regular townspeople who raised their statuses to become innovative powers of the time were also called to serve as otogishu. They became new culture bearers during the reign of Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1536 – 1598). At the height of his rule, Hideyoshi Toyotomi had over 800 otogishu working for him serving wide range of purposes. If he needed to prepare for a battle, he had a specialist in war stories to inspire him. If he needed to unwind, he would consult a specialist in funny stories, and if he needed wise counsel, he would consult a former Buddhist priest. One of the best speakers around him was a Buddhist priest named Anrakuan Sakuden (1554-1642). Anrakuan Sakuden was a Buddhist priest of the Pure Land sect based at Kyoto’s Seigan temple where he was the head monk. He was also tea ceremony devotee, camellia connoisseur, and dilettante poet. Anrakuan even derives his name from the name of the tea house he built himself. He compiled a joke book called Seisuishou (“Laughing to Keep You Awake”). Released in 1623, this eight-book series contains 1039 jokes. The Seisuishou is regarded as a major forerunner of the popular Edo-period literary genre known as hanashibon, or books of humorous stories. Because of this, Anrakuan Sakuden is known as the “Father of Rakugo,” a form of comic monologue performed by storytellers, still popular to this day.

A bit later, also in Kyoto, another monk by the name of Tsuyu No Gorobei (1643-1703) was telling tsuji-banashi (“crossing stories”) in the street. Before beginning his stories, he would gather passers-by around him, which he accomplished with the help of a small table known as a kendai and two pieces of wood. The kendai and the pieces of wood are still used today in the Kamigata Rakugo style (the Kansai style) to give rhythm to the story and to show a change of scene. Meanwhile, in Edo (old Tokyo), Shikano Buzaemon (1649-1699) was telling zashiki-banashi (“stories of the tatami room”). This enclosed environment later led to yose, the cabaret where one can still listen to rakugo even today. He wrote Shikano Buzeamon kudenbanashi (“Shika no Buzaemon’s Oral Instruction Discourses”). He was also the author of Shikano makifude (“The Deer’s Brush”) which contained 39 stories, 11 of which were related to the kabuki milieu.

The otogishu aided Hideyoshi’s reign in domestic affairs and gave rise to the magnificent Momoyama (“Peach Hill”) Culture which reflected emerging samurai forces and the economic power of merchants. It was also the otogishu who also contributed to later Japanese culture, such as the completion of wabicha (wabi style of tea ceremony) that pursued simplicity. After the Edo period, the shogun and territorial lords retained otogishu; however, as political power shifted to chief retainers, otogishu’s power gradually dwindled. Their storytelling, however, spread among the common people and became the origins of kodan storytelling and rakugo.

Later in the Edo period, the practice of storytelling grew in popularity. Storytellers recited these stories in the street before moving on to the yose, a special performance space, in 1791. Hundreds of stories were added to the repertoire over time, which rakugoka still use to this day. Rakugo became increasingly popular among the lower classes as it was introduced to various classes as a result of the establishment of the merchant class during this era. Groups of rakugo performers were formed during this time, and text collections were printed. The people who wrote down the stories told by the rakugoka at this time, and throughout the 17th century, was known as the hanashika, which literally translates to “translating the storyteller.”

Several artists have contributed to the development of this storytelling art form over the years. Apart from Anrakuan Sakuden himself, there was Shikano Buzaemon, who lived in Edo, which is now known as Tokyo, from 1649 to 1699, was another significant contributor to this form of storytelling. Shikano Buzeamon kudenbanashi, or Shikano Buzaemon’s Oral Instruction Discourses, was written by him. Shikano was also the author of Shika no makifude, or The Deer’s Brush in English, which contained 39 stories, 11 of which were related to the kabuki milieu.

In 1693 a cholera epidemic broke out in Japan that claimed 11,000 lives. During this national emergency, a ronin (a samurai without a master) and a greengrocer devised a scheme to defraud innocent people. They attempted to carry out their cunning plan by telling people this story: “There once was a talking horse. One day, this horse prophesied that umeboshi (Japanese plums) will protect you from the plague! We have a lot of umeboshi! Buy one, get one free!”. This led to a price explosion for umeboshi. Although it was not a very convincing scheme, the culprits were soon apprehended. The ronin was executed and the greengrocer was imprisoned in a remote island. However, before they received their punishments, they admitted that they had the idea for this talking horse scheme from one of Shikano’s joke books. Shikano was then exiled to Izu Ohshima Island and died there – a tragic end for someone who helped to establish rakugo in Edo.