“Each of the criminals is bound to an iron pillar and the ox-headed demon is in the process of administering punishment—using iron or copper blades he peels the skin of the person’s face, just as a butcher kills a pig and then flays it.” This passage is found in a Chinese Shanshu (“good book” or “morality book”) titled Diyu yu–chi (roughly translated as “Record of a Journey to Hell”). The book emerged in tenth century China and talks about the things that one would find in hell which, of course, include many forms of tortures.

The underworld in Chinese Mythology, Diyu (literally means “earth prison”), is where the souls of the deceased are held accountable for their actions in life before they are reincarnated. The exact number of levels in Diyu and their associated deities differ between Buddhist and Taoist interpretations. Some speak of “Ten Courts of Hell”, each of which is ruled by a judge, and others speak of the “Eighteen Levels of Hell”. Each court deals with different punishments and a different aspect of atonement.

However, the underworld in Chinese mythology has an interesting concept that distinguishes it from the other cultures. According to the ancient Chinese belief, the underworld is simultaneously a place of vicious physical tortures and a particularly nasty and intractable bureaucracy – the sixth court of hell, for example, is named “Screaming Torture and Administrative Errors”

The underworld is thought to be a duplicate or alternate version of the Earthly realm. It has a city wall, palaces, a hall of justice, and various houses for the ghosts of the dead. Especially important is the housing for the official records, which allow the various judges to determine proper punishments or to occasionally allow someone who dies before their time to be returned to life.

The underworld is teeming with souls who are passing through on their way to being reincarnated back into the world of the living. These waiting souls are being looked after by their living descendants who burn paper offerings to them at their funerals. The paper offerings include items such as houses, horses, and money that are meant to ensure that the soul of the deceased would have a pleasant stay in the Underworld realm and enjoy the same facilities there that the living enjoy in the earthly realm.

The capital city of the underworld is named Youdu (“Dark Capital”). You can also mean “hidden” or “secluded”. Youdu is generally conceived as being similar to a typical Chinese capital city, except that it is pervaded with darkness. Although there are many functionaries which have been believed to inhabit the underworld, the more important individuals being located in Youdu, as the capital city and the seat of the underworld’s government.

The most important feature of this city are the place of Yan Luo. Beneath him in rank ten magistrates who serve as judges of the souls of the dead in the Ten Courts of Justice. There are also many subordinate demons which serve to carry out the commands of the judges. These demons are concerned with punishing or processing the souls of the dead for reincarnation.

It is helpful to understand that the ancient Chinese conception of gods is based on the Chinese bureaucracy. The social organization of the human government is the essential model that the ancient Chinese use when imagining the gods. At the top of the divine bureaucracy stands the Heavenly Emperor, or the Jade emperor in Heaven, who corresponds to Tianzi, the human Son of Heaven, which is another name for emperor who rules over earth. The Heavenly Emperor is in charge of a massive administration which are divided into bureaus, and each bureaucrat-god is responsible for a clearly defined domain or function.

The local officials of the celestial administration are the City Gods, or the Gods of Walls and Moats – each City God is responsible for one locality. Working under them are the Kitchen Gods, also known as the Gods of the Hearth. There is one Kitchen God per family who generate an eternal flow of reports on the people under their jurisdiction. The Kitchen Gods are assisted by gods believed to dwell inside each person’s body. They accompany people through life and into death, also carrying with them the records of good and evil deeds committed by their charges.

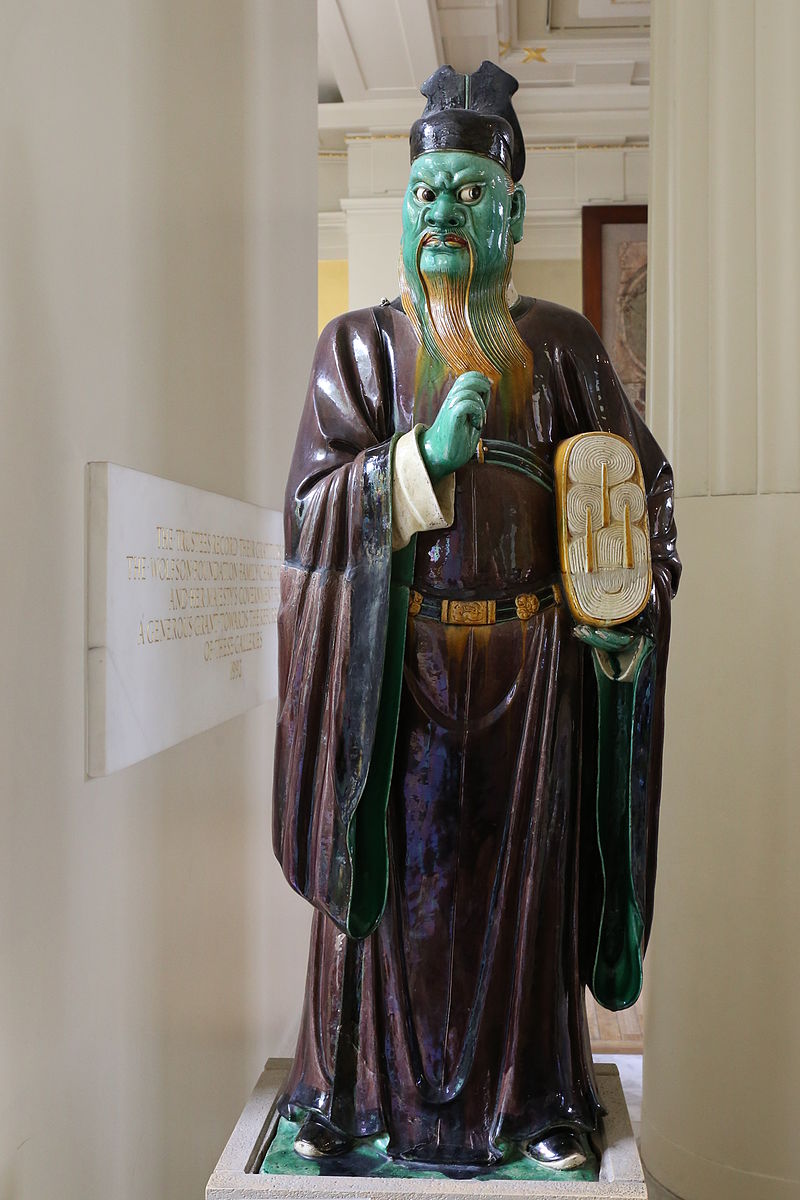

The Ten Magistrates of Hell are those who administer punishment to deceased spirits passing through the Underworld. Each magistrate had control over a specific “hell”. They are assisted by ferocious assistants who aid them in the execution of the various punishments. The various punishments inflicted by the Hell Magistrates’ assistants, along with the layout of the ten (or eighteen, by some accounts) hells of the Underworld, were very commonly known in late-imperial China.

A graphic depiction of the Chinese concept of the underworld can be found in a small Buddhist temple in Hu County, Shaanxi Province. Bearing similarities to the Egyptian Court of Osiris, it graphically depicts the fate of the wicked before they are reincarnated into another life.

The main figure of this mural is the god of death, and the ruler of hell, Yan Luo. He stands in priestly robes waiting for the soul of the deceased to be brought before him for judgment. Yan Luo has two assistants, “Ox-Head” and “Horse-Face”, who meet the soul as soon as it enters the underworld. In a scene similar to the Egyptian portrayal of Osiris and his cohorts, Anubis and Thoth, they escort the wicked soul to Yan Luo for judgment.

According to tradition, Yan Luo was originally assigned to the First Court of Hell. However, he proved to be too sympathetic and lenient. Therefore, too many souls were crossing the Golden Bridge to heaven. As a result, Yan Luo was reassigned by the Jade Emperor to the Fifth Court of Hell – the Hell of Wailing, Gouging and Boiling. Over time, Yan Luo developed a taste for punishing dead souls.

How a person dies is said to impact how he is brought into the underworld and how long he will remain there. If he dies a natural death, his soul is brought to the guards of hell, where he is chained and marched into the underworld. However, the soul is allowed to return to the mortal world to visit his family and loved ones in seven days. In the mean time, the deceased’s family prepare offerings of food and burn “hell money” to distract the guards in order to give the deceased more time to be with his family.

If a person dies accidentally, the soul will be confused and will wander for several days. After seven days, he will learn that he has died and will try to return to his family. The guards of hell, who have been waiting for the soul at his family’s home, will escort the deceased into the next plane of existence to be judged. If the person dies a brutal death, or if he commits suicide, his soul is consigned to spend eternity in a state of rage and anger. The guards will not come for him and the soul will be required to relive its last moments again and again throughout eternity. The place where the brutal death occurred is considered haunted by the living. To cleanse such a location, a monk will be called in to perform an exorcism. However, this is considered a risky undertaking as the soul is always angry and often vicious.

Upon their deaths, most souls are escorted into the halls of hell. There, they will meet thousands of other souls who have also recently died. They will also witness the punishment being carried out on the souls of those condemned as wicked. The soul will be brought before the Mirror of Retribution (the First Court of Hell) where, in the mirror’s clear and polished face, the life of the deceased will be replayed. If the person lived a righteous and caring life, they will be allowed to progress to heaven to live in happiness. More often, however, the souls are found guilty of selfishness, greed, and other transgressions, and will be assigned another level of hell for judgment and punishment.

After reflecting on one’s past sins through the Mirror of Retribution, the next levels of hell include drowning in the Pool of Filth and the Hell of Ice, entering the Black Rope Hell and the Upside-Down Prison, being submerged in the Lake of Blood and tortured by bees, go through the Sixteen Departments of Heart Gouging, Screaming Torture and Administrative Errors, Torture by Mincing Machine, Hot Suffocation Hell and, lastly, Iron Web and Office of Fair Trading. When one’s torments are over, the now clean soul is summoned to the Tenth Court, the Wheel of Rebirth, where the manner of one’s next existence is decided. The soul will then be move up or down the spiritual ladder, depending on their actions when they were alive. The wicked may return as an animal or insect, while the good will return as a human. Then Mother Mèng Po administers the Tea of Oblivion, which erases one’s memory and ensures that all the punishments are forgotten. The dead spirit is now ready to be reborn in a new earthly incarnation.

Depictions of a Chinese underworld can be traced back to commemorative inscriptions found on bronze vessels in Shang and Zhou tombs (c. 1600-256 BCE) which reference an “underground” realm inhabited by the deceased. More detailed references to this underground domain populated by the deceased are from the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-256 BCE), where it was alternately referred to as the Huangquan (“Yellow Springs”) or Youdu (“Dark City”).

Zuozhuan (“The Chronicle of Zuo”), a narrative history which details this Eastern Zhou period, mentions the underworld in a tale about the Duke of Zheng. The Duke, angry with his disloyal mother, threatened not to see her until they met again at the Yellow Springs. After his mother’s death, the guilt-ridden Duke dug a tunnel in hope of reuniting with his mother. However, his success in this endeavor, or any additional information about this underground realm, has not surfaced within the known historical record. The term Dark City, evoking images of an underground tomb or underworld, first appeared in an anthology of poems from the Warring States period titled Chuci (“Songs of the South”).

Major developments in the systemization of models of the underworld occurred during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Chinese folk religion before the Han period seems not to have had the concept of sin, although it recognized a great number of supernatural beings. Although complex demonographies, used by shamans to identify and control harmful spirits, have been dated as far back as the Warring States period, it was not until the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–24 CE) that an official bureaucracy of the underworld was developed.

This hellish bureaucracy mentioned in this period featured a Lord of the Underworld, an Assistant Magistrate of the Underworld, an Assistant of the Dead, a Retinue of the Graves, a Minister and Magistrate of Grave Mounds, a Commander of Ordinance for the Mounds, a Neighborhood Head of the Gate of the Souls, the Police of the Grave Mounds, a Marquis of the Eastern Mound, a Count of the Western Mound, and an Official of Underneath. The third century BCE text, Chunqiu Shiyu (“Chunqiu Affairs and Speeches”) focuses on the untimely deaths of political protagonists who were portrayed as having posthumous careers as bureaucrats in the underworld.