Richard Wagner’s 19th century opera, Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of Nibelungen), affectionately known as the “Ring” Cycle, may be considered by many as the height of operatic absurdity, with larger than life staging, costumes and voices. The image is so ingrained in the modern consciousness that opera lovers and non-lovers alike associate the opera, specifically the character of Brunhilde, with a heavy-set female opera singer wearing her hair in pig-tails, costumed with horned helmet and armor. As the opera went on to make its mark on popular culture, from featuring in an episode of Bugs Bunny to inspiring a Quentin Tarantino film, Brunhilde became a more visually recognizable figure, which is not always followed by immediate association to her name and her story.

Brunhilde is an ancient character who can be traced back to Norse mythology. She is a shield maiden and, mostly due to her presence in German literature and the modern media, arguably the most famous of the Valkyrie. Before being made famous by Wagner, she appears as a character in the Eddic poems and the Volsunga Saga, as well as in the Nibelungenlied (The Song of the Nibelungens), a German epic of the 1200s.

The story of Brunhilde and Sigurd the dragon-slayer is considered by many as one of the oldest and finest of the Norse Mythology. However, like any old and beloved story, it became the subject of a widespread oral tradition, leading to many broadly similar versions. Versions of this story differ according to the time in which they were written and the character of the listeners or readers of the myth. Local bards simply adapted the story as they saw fit, resulting in many variations.

The first mention of Sigurd and his daring deeds is found in the song of Fafnir, in the Elder Edda, the first collection of Eddic poetry. It is repeated in the Younger Edda, in the myth of the Niflungs and the Gjukungs, before being told again in the Volsunga Saga of Iceland. It was then repeated in various forms and different languages until it finally appears in the epic German poem Nibelungenlied. An early critic labeled it a German Iliad, arguing that, like the Greek epic, it goes back to the remotest times and unites the monumental fragments of half-forgotten myths and historical personalities into a poem that is essentially national in character. In this last version, Sigurd is known as Siegfried and the story is colored and modified by the introduction of many notions peculiar to the middle ages.

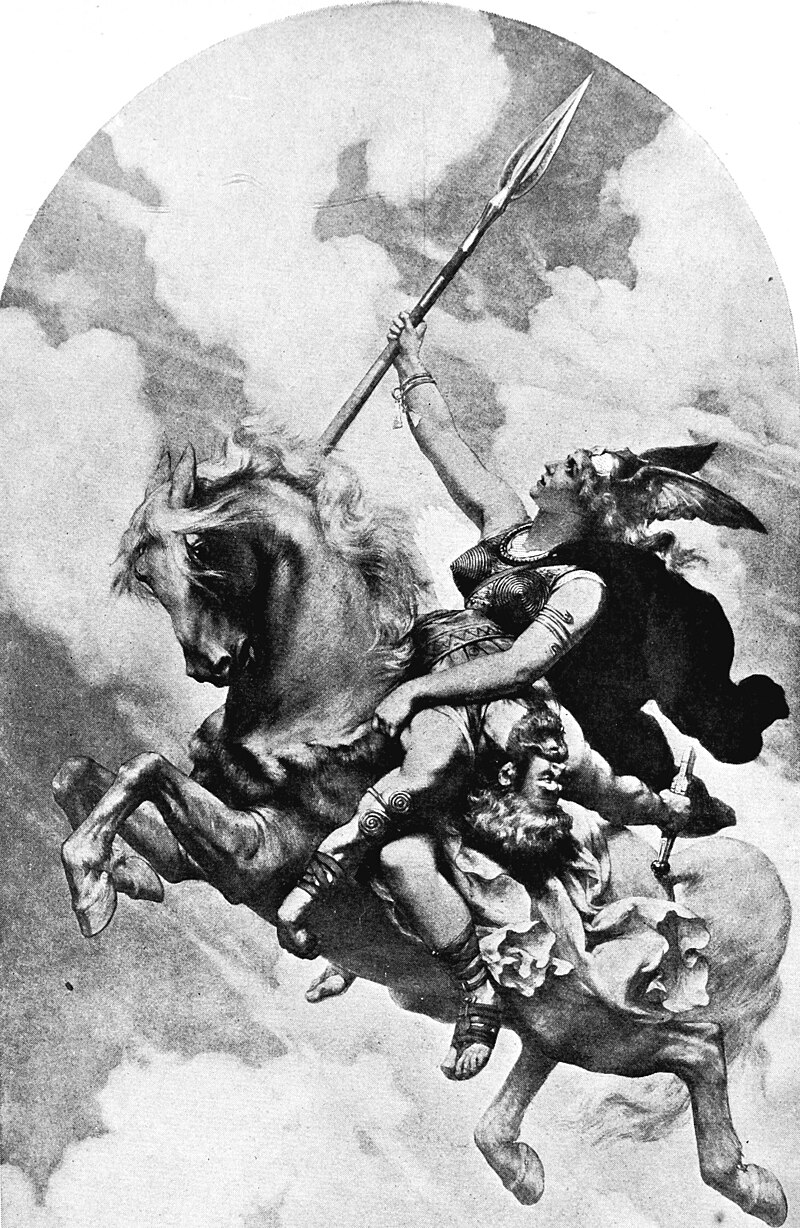

In legend, Brunhilde is a Valkyrie. With her eight sisters, she roams battlefields searching for fallen heroes whom she takes to Valhalla, a grand hall in the Norse afterlife.

One day, Odin orders her to decide the outcome of a fight between two kings, Hjalmgunnar and Agnar. Although she knows that Odin prefers the older king, Hjalmgunnar, Brunhilde sides with Agnar. This angers Odin, and he condemns her to live the life of a mortal woman, imprisoning her behind a wall of shields on top of mount Hindarfjall in the Alps where she must sleep until a man rescues and marries her. As a Valkyrie, Brunhilde has sworn an oath of chastity, but the oath becomes void when Odin takes away her powers. Still, she is determined to only marry the best of men. Odin grants her wish and decrees that she is to be surrounded by a circle of fire so that only a man who knows no fear can pass through to reach her.

The hero Sigurd, heir to the clan of Volsung and slayer of the dragon Fafnir, enters the castle and awakens Brunhilde by removing her helmet and cutting off her armor. He claims her as his bride and the two fall in love. But Sigurd has to leave her there, since he has many tasks he must perform. He promises to return and make Brunhilde his bride after he completes his tasks. Brunhilde agrees and says she will wait for him within the Ring of Fire, promising that she would marry no other but the man who would ride through the flame.

As a token of his promise to her, Sigurd then gives Brunhilde his magic ring, called the Andvaranaut. It is a ring of power that once belonged to Odin himself. Unbeknownst to Sigurd, a curse has been placed on the ring so that anyone who possesses it will die. Brunhilde gives Sigurd her armor, her horse and her wisdom. The lovers pledge eternal fidelity to each other and, armed with Brunhilde’s knowledge and battle gear, Sigurd sets out into the world to make a name for himself.

After some time, Sigurd arrives in a kingdom at Worms on the Rhine. Here he meets the king, Gunther, his sister Gudrun, and his aid Hagen. Gunther has heard of the wise and beautiful Brunhilde and wants her for his wife. Gudrun sees the brave and handsome Sigurd and wants him for a husband. The siblings then conspire to give Sigurd a magic potion that will make him forget Brunhilde and fall in love with Gudrun. Sigurd drinks the potion, falls in love with Gudrun, and asks Gunther for her hand. Gunther agrees to the match if Sigurd helps him win Brunhilde.

Forgetting his own relationship with her, Sigurd disguises himself as Gunther and passes through the flames to claim Brunhilde as Gunther’s bride. Brunhilde, although disappointed that it is not Sigurd who comes for her, has no other choice but to marry Gunther. As proof of her promise, she gives the magic ring to Sigurd, thinking that it is Gunther that has taken her ring. Sigurd then brings her to Gunther’s court and leaves to resume his own form. Gunther and Brunhilde are soon married, while Sigurd marries Gudrun.

One day, Brunhilde sees the ring on Sigurd’s finger and realizes that Sigurd has betrayed her. She is outraged and plots Sigurd’s death with the aid of Hagen and Gunther, revealing to them tat Sigurd can only be killed from the back. Hagen, therefore, attacks Sigurd from behind with a spear – killing him dishonorably.

Only after Hagen murders Sigurd does Brunhilde learn the truth – not only was Sigurd innocent, but all the events leading to his death had been orchestrated by Odin in hopes of retrieving his magic ring.

Brunhilde orders that a pyre be built and Sigurd’s body be placed on it. She takes the ring from his finger and puts it on her own. She then sets the funeral pyre on fire, and rides her horse onto the pyre to die with Sigurd. The flames rise and engulf Valhalla, destroying Odin and the gods, removing the curse of the ring and redeeming humankind from the arbitrary rule of the gods.

The Nibelungenlied combines oral traditions of Sigurd and Brunhild, and reports based on historic events and individuals of the 5th and 6th centuries. Prevailing theories suggest that the written Nibelungenlied is the work of an anonymous poet, likely to be a man of literary and religious education at the bishop’s court. His audience, then, would very likely be the clerics and noblemen at the same court.

The story tells of Siegfried the dragon-slayer at the court of Burgundi, his deception to Brunhilde, his subsequent death and his wife Kriemhield’s revenge. The epic is divided into two parts, the first dealing with the story of Siegfried and Kriemhild, the wooing of Brunhilde, and the death of Siegfried at the hands of Hagen. The second part deals with Kriemhild’s marriage to Etzel, her plans for revenge, the journey of the Burgundians to the court of Etzel, and their last stand in Etzel’s hall.

The poem in its various written forms was lost by the end of the 16th century. However, manuscripts from as early as the 13th century were rediscovered during the 18th century.

Imagery from the Nibelungelied was used in many poems, essays, posters and speeches at every stage in the development of German nationalism, from the Befreiungskriege (Wars of Liberation,) the regime of National Socialism, to many other interpretations and references today. The story also gave birth to an expression, Nibelungentreue. The English equivalent of this expression would be “The blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb,” where the faithfulness among the king and his vassals ranked higher than family bonds or life. This expression was used in Germany before World War I to describe the alliance between the German Empire and Austria-Hungary.

In 2009, the three main manuscripts of the Nibelungenlied were inscribed in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in recognition of their historical significance.

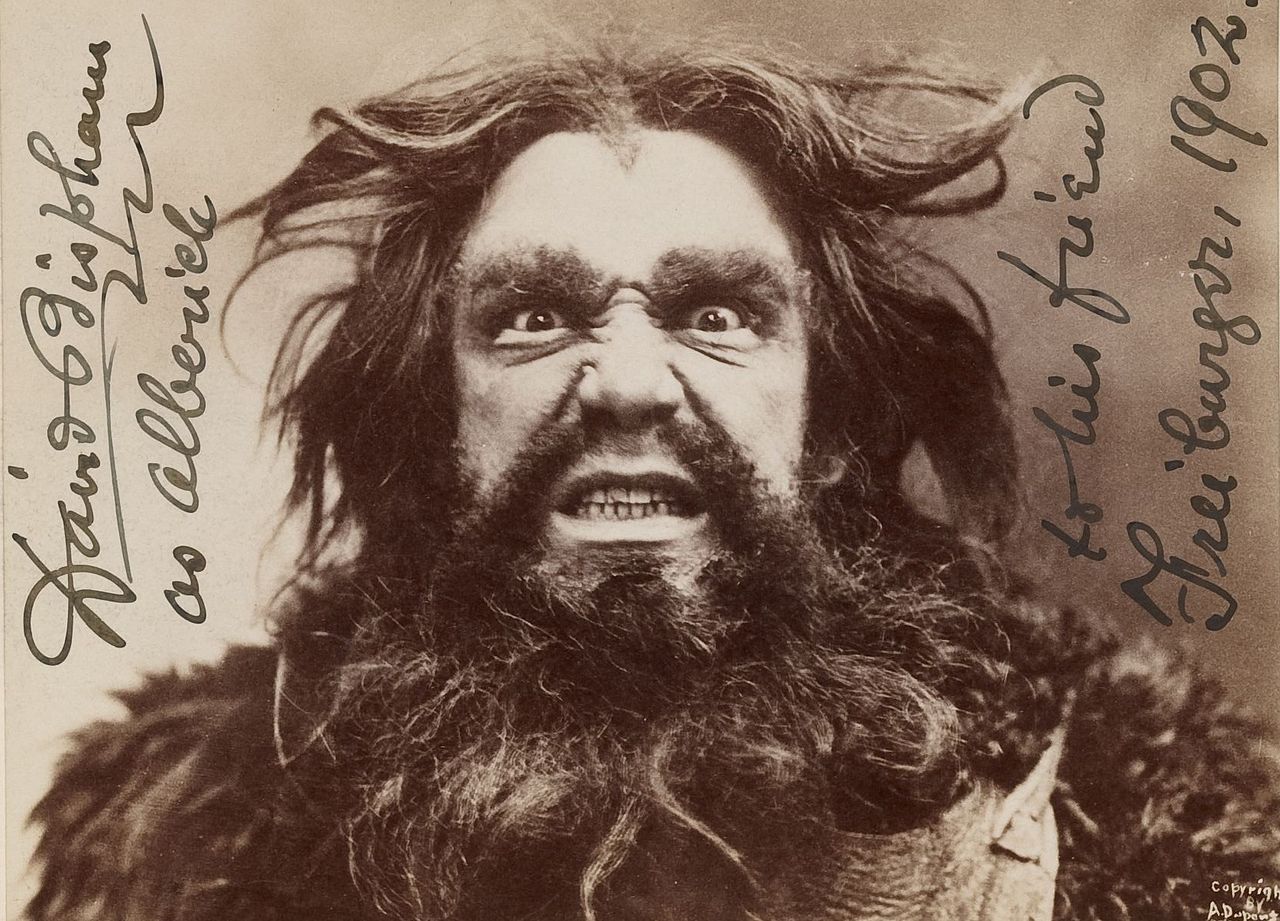

Although operatic composer Richard Wagner’s cycle of four operas is titled Der Ring des Nibelungen, he took Brunhilde’s role mostly from the Norse sagas rather than from the Nibelungenlied. Brunhilde appears in the latter three operas playing a central role in the overall story of Wotan’s (Odin) downfall.

Her distinctive characterization and costuming in the “Ring” Cycle turned Brunhilde into the epitome of a stereotypical operatic character. This may have given birth to the expression “it ain’t over till the fat lady sings” which means nothing is irreversible until the final act is played out. The musical connection is with the operatic role of Brunhilde in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, the last of the very long “Ring” Cycle, where she is usually depicted as the lady who appears for a ten-minute solo to conclude proceedings. “When the fat lady sings” seemed to be thought of as a reasonable answer to the question “when will this opera be over?” which must have been asked many times during Ring Cycle performances, lasting as they do upwards of 14 hours.

Brunhilde’s image as the “fat lady” of the opera did not come about accidentally. For centuries, opera singers have been viewed as cartoon-like, obese people with big voices that could shatter glass. Many opera devotees, for example, fondly refer to “Madame Butterfly”, one of the most famous operas and diva roles, as “Madame Butterball”. This image came about due to the demands of the art at the time. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, opera was an expanding medium. Successive generations of opera producers, including Wagner, sought larger and more dramatic effects in operas, larger audiences, and larger theatres. Therefore, better vocal techniques were developed to better cope with this steady rise in size and volume of opera productions. New technology for wind instruments and the reconstruction of older baroque string instruments also came about as the result of these innovations.

It was also in this period that a bigger frame was viewed as desirable for an opera singer. There are several theories attempting to explain this. One theory holds that a large amount of fatty tissue surrounding the larynx increases its resonance capability and thus produces a more pleasing sound. Although the amount of this fatty tissue varies from singer to singer, it is impossible to have a great deal of fatty tissue around the larynx without carrying fatty tissue elsewhere on the body.

A second theory is that opera singers need a far more powerful diaphragm than normal to be able to project their voice above the sound of a large orchestra in a large opera house. A large chest cavity and good control of the lungs will provide a suitable mass to help drive the diaphragm to some extent. A large body mass and a large body frame to support it will help even more. Therefore, there is an advantage in having a larger-sized body.

A more recent theory, published in 2001 by Dr. CW Thorpe from the National Voice Centre at the University of Sydney, says that the act of opera singing itself expands the body, particularly the rib cage. After years of singing, the opera singer’s body may look bigger than it really is.

In the middle of all these innovations, the ‘elite’ opera singers were, and still are, those who perform in Richard Wagner’s operas, which require a full orchestra and are notoriously difficult for singers to project over. Wagner created his own theater in Bayreuth, Germany that covered half the orchestra to mute the sound. Not all opera houses are built the same way, so Wagnerian singers are required to sing even louder than the composer originally intended. Those with large rib cages and the ability to expand them, therefore, sing with more volume and power.

Composers of the baroque, classic, and early Romantic periods favored smaller orchestras and thinner instrumentations. The roles in these operas require a different talent to Wagnerian operas. Just like an athlete, singers are either more flexible or strong. Lighter operas require more flexibility, such as in George Frederic Handel’s Messiah while Wagnerian operas require more strength. Media’s constant usage of Brunhilde to represent opera singers can give the impression that more opera singers sing Wagner than not. In actuality, they represent only a few elite singers. To this day, only very few opera houses have the budget and ability to perform Wagnerian works, and good Wagnerian singers are a rare commodity.

The character of Brunhilde may have evolved from a legendary mythological character to a sometime-ridiculed operatic role. Yet, not many other mythological figures can claim that same distinction. She may have been eclipsed by other characters in the Norse mythology such as Odin or Sigurd, but she endured and remains relatable in the modern age as her story is something that many modern women can relate to: the overly-demanding father figure, the strong sense of responsibility at a young age, the fear of being stripped of her stature and position of power, the fear of losing her beauty and magic, and the fear of becoming enslaved and ruled by an unworthy husband.