Ephippus, in a surviving fragment of his lost pamphlet depicting the court of Alexander the Great in 324-323 BC, alleges that Alexander liked to cross-dress as the Greek archer-goddess Artemis. Supposedly, Alexander often appeared in public as Artemis dressed in the Persian garb with a bow and hunting-spear. It is likely that the passage is a libel, possibly to denounce Alexander. As his father Philip had destroyed Epipphus’ home city of Olynthus in 348 BC, Epipphus may not have been too fond of the young king.

Epipphus’ choice of slander left room for a wide range of interpretations. Seeing this from a modern perspective, Epipphus’ way to demean Alexander may be the allegation that the mighty king Alexander was a cross-dresser. But, what if Epipphus meant to ridicule Alexander the king for presumptuously impersonating a deity – an activity reserved for priests? This would illustrate what seems to be ancient society’s attitude towards cross-dressing.

Crossdressing is recorded around the world from the ancient past up to the present. In the ancient world, cross-dressing often mirrored gender-crossing actions of deities. In this context, it was tolerated, even supported, as an aspect of religious devotion. Also in this context, the transformation of gender is often associated with the process of coming closer to divinity by breaking down the categories of ordinary human experience. The manipulation of dress, therefore, is the most visible and convenient way for human beings to do what divine beings accomplish by other means, including crossing gender.

The Sumerian deity Inanna, identified with the Akkadian Ishtar, is believed capable of either gender presentation to bridge heaven and earth as well as gender-altering power.

Her cults included the kurĝara, whose dress incorporated mixed gender elements in their public processionals. Atum, of ancient Egypt, could be depicted androgynously, as said in a coffin text which says “I am the great He-She”. But perhaps the best known example of a divine gender-bender was Dionysus. Greek literature scholar Albert Henrichs called Dionysus “the most versatile and elusive of all Greek Gods,” as he was perceived as both man and animal, male and effeminate, young and old.

As there are many legends about Dionysus, there are varied depictions of Dionysus ranging from bearded Dionysus to more effeminate versions. Archaic vases show him in a woman’s tunic, saffron veil, and helmet. Dionysian festivals frequently featured role reversals such as cross-dressing. In the festival of Oschophoria, for example, young, wealthy noblemen dressed as women and led a sacred procession from the Temple of Dionysius to that of Athena.

Deities often take disguises. Frequently the disguise involves appearing as a gender different from the one typically associated with that deity. Athena, for example, in Homer’s Odyssey disguises herself as Mentor, the male friend of Odysseus. Zeus disguised himself to appear like Artemis. His aim was one of those familiar to gender-crossings for thousands of years to come, which is to gain an access he would have otherwise lacked. In this case, it was access to the nymph Callisto.

In the East, Vishnu took the form of an enchantress named Mohini to distract some asuras (demons). On another occasion, Vishnu utilized the same guise to rescue the god Shiva by distracting a another demon.

Later, Shiva and Vishnu engaged in a sexual encounter that left Vishnu-as-Mohini pregnant. Their child was the hermaphroditic deity, Ayyappan (or Hariharaputra). The Tamils know a group of male devotees of Vishnu-as-Mohini, called the ‘Ali,’ who cross-dress and whose principal religious ritual has this story at its center. A variety of other occasions and manners existed by which to honor Mohini. The Hindu Mohini Attam, or the dance of the enchantress, commemorates the story of Vishnu’s cross-gender appearance as Mohini to save Shiva.

In many religions, cross-dressing might be done for a variety of reasons. Shamanism utilizes crossdressing as part of the transformation by which a shaman mystically transcends the boundaries of gender and day-to-day reality. The unity of male and female in one’s own person is frequently represented in the clothing the shaman wears. The Siberian shaman, for example, wears a caftan (a unisex garment) decorated with iron disks, bars, and other items which symbolize various aspects of nature, such as the human body, including two orbs for breasts. Anthropologists early in the 20th century observed that among the Siberian Yakut the male shaman, when not in his costume, wore a woman’s dress fashioned from the skin of a foal.

In ancient Sumeria, the cross-dressing priests, kurĝara, may have been a template for later gender-crossing priests, such as the male assinnu of Ishtar, or the “male shrine prostitutes” referred to in the Jewish and Christian sacred literature (1 Kings 12:24). The ‘Galli,’ priests of Cybele, also cross-dressed and sometimes castrated themselves in their imitation of the revered figure of Attis.

In Korea, female shamans wear male clothing. The male shaman in Korea (paksu mudong) performs kut wearing women’s clothing down to the pantaloons. In the Philippines, there were male shamans (the Bayog) who appeared as women in dress, hairstyle and effeminate behavior.

It was only a matter of time that gender-crossing proved to be necessary in one’s social life. In ancient China, “female” was considered to be subservient to “male”. This would have proved to be rather confusing when the “female” occupied an undeniably powerful station in society, such as an empress. Thus, in the Analects of Confucius, the wife of the ruler of a State is referred to by the ruler as “That Person” or “That person of the Prince’s.” The emperor’s wife may not be referred to by any term that is feminine and must use a masculine term to refer to herself. Due to the inflexibility of social relations, a flexibility in gender designation was demanded to protect the social order. During the T’ang Dynasty, Empress Wu Zetian (624 – 705 CE) declared herself ‘Son of Heaven’.

Even prior to her attainment of supreme power, Wu had occupied the role of an advisor to the throne, even sporting a beard herself like other male advisors.

The religion from which ancient Greek theater developed was the worship of Dionysus, whose rites were carried out principally by women. However, when these rites evolved into theater and performances, women were banned from the stage and men took on the women’s parts. The theater was grounded in religion and having women on stage was not considered decorous even in ancient times. Ancient Greek society had perhaps seen the “danger” of female sexuality through the ecstatic dances shown in the worship of Dionysus.

The ban against women on stage remained in force until the 17th century when female singers began to appear in operas. Rather than condone female performers, the Church employed male castrati to sing soprano parts. The Castrati continued to perform in the papal choir until the late 19th century. When women were finally allowed to perform on stage, they also got to play roles of the opposite gender. During the Restoration period, it became a vogue for women playing roles such as Macheath in John Gay’s “The Beggar’s Opera.”

Also popular at this time were women playing young boys, especially those characters whose appealing vulnerability could be enhanced by casting a woman in the role such as Peter Pan, the brave little boy who deep down is very lonely. Other cross-dressing roles were created due to the need for an adult male character to seem other-worldly such as Orpheus in “Orfeo ed Euridice” or unmanly, such as Prince Idamante in “Idomeneo”. An artistic reason for “pants roles” or “trouser roles” (where male characters are played by women) was that although some stories required young boy characters with a boyish voice, the actual performance required an adult’s vocal strength and stage experience. Women were therefore considered to be better suited to these boy roles than actual boys.

In these cases, gender impersonation was not seen as an attempt to imitate the other gender, but as an effort to combine elements and create something new and cannot be easily experienced outside the theater. An historical example of an actress famous for trouser roles is Julie d’Aubigny, or “La Maupin” (1670–1707), and some female opera singers specialize in these roles even to this day.

As it was illegal in Renaissance England for women to perform in theatres, female roles in the plays of Shakespeare and his contemporary playwrights were played by cross-dressing men or boys. Therefore, the original productions of Shakespearean plays such as “Twelfth Night” and “As You Like It” actually involved double-cross-dressing, where male actors would play female characters disguising themselves as males.

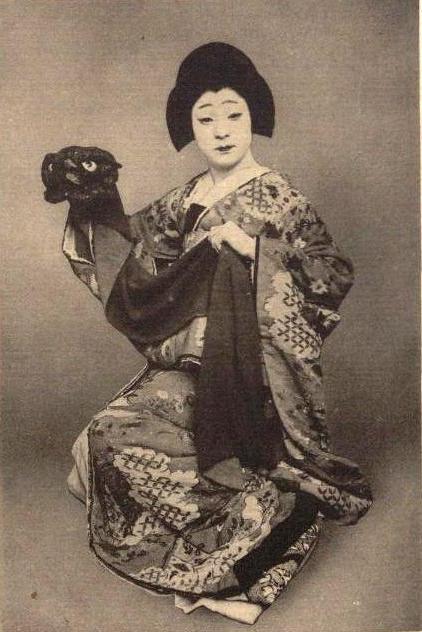

The Japanese Kabuki theater began in the 17th century with all-female troupes performing both male and female roles. In 1629 the disrepute of kabuki performances (or of their audiences) led to the banning of women from the stage, but its great popularity inspired the formation of all-male troupes to carry on the theatrical form. In Kabuki, the portrayal of female characters by men is known as onnagata.

China has a 13-century-long tradition of the acting skill of cross-dressing. Many male and female performers even extended this stage practice of cross-dressing offstage and wore the clothes of the other gender on a daily basis. Men and women cross-dressed in the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368 CE) even as they performed side by side on the same stages.

The earliest record of kunsheng (female men, or actresses playing male roles), appeared in the middle of the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE). In Qinglou ji qianzhu (“Green Bower Collection”), written circa 1341-1368, author Xia Tingzhi recorded the artistic activities of 117 actresses, many of whom were successful male impersonators. These kunsheng were not only capable of performing male roles that required strong singing voices, but they also portrayed military male figures, demonstrating their mastery of martial arts and acrobatics. Yuan dynasty actresses even impersonated male characters in mixed-sex theater troupes, which further proved their artistic expertise and popularity.

The activities of kunsheng reveal that in the Yuan period a performer’s gender was not the main consideration for the role they played onstage. A character’s gender was represented through dress and gesture, and the external determinants of dress and gesture were the way in which the culture regulates gender differences-in everyday life and on the stage. And because these external determinants could be put on and taken off, they were then manipulated by artists onstage and were recognized by the society as art.

In the late 18th century, the Manchurian rulers banned public performances by women. Under this edict, male cross-dressing became an unavoidable strategy to regulate gender difference. This new rule led to a controversial social practice. In the 19th century, Qing law forbade government officials to visit female prostitutes, as the theater and prostitution were viewed under the same banner of “performing arts” and therefore not suitable places for women. Because of this, boy actors became substitutes.

This prohibition on women prostitutes caused the rapid expansion of a special brothel called xianggong tangzi (the house of female boys), which were found on every corner of Beijing in the middle of the 19th century. In these brothels, men paid to have sex with young boys who were usually costumed as female characters from Chinese opera. As xianggong tangzi became more popular, many young boys were sold to them to help their poor families. The boys were trained in various acting techniques required for female roles in the theater, and many of them eventually grew up to become professional actors.

However, women gradually came back to the stage, and from early 20th century, Shaoxin opera is developed from all male to all female genre. Although male performers were introduced into this opera in 1950s and 1960s, Shaoxin opera is still associated as the only all-female opera and the second most popular opera in China today.