The Olympics took place every four years for more than a millennium. One of the aspects of culture regarded as distinctive to the ancient Greeks was their pursuit of sport. Apart from its function as the act of worship to Zeus, athletic competition, particularly at the major Pan-Hellenic sites, was also a means for the ancient Greeks to promote and celebrate their ethic bonds. Historical records tend to give the approximate confirmation of the Olympic starting date as 776 BC, which would place the first Olympic as several decades before the use of the Greek alphabet and Homers Iliad.

However, as important as this was to the Greeks, participation in the Olympics was open primarily to men and boys. In fact, one of the big themes of sport in ancient Greece was the separation of the genders and emphasizing the different traits between men and women. Women were discouraged to participate and extreme laws were in effect to stop married women from attending the Olympics. However, this did not stop the ladies from having their own athletic competitions, even competing against the men and winning.

While there may have been societal pressures and divisions in sport due to gender that hindered a woman from engaging in athletic competitions, women in ancient Greece still did many physical activities, and they competed with each other – albeit not at the Olympics. Homer’s Odyssey and Xenophon’s Symposium describe women playing with balls, driving chariots, swimming, and wrestling and running.

Therefore, while the idea of a sporting event for women were not considered taboo, it was the idea of the women competing at the same level, manner and event as the men which posed difficulties. The celebration of the Heraea at Olympia, held to worship the goddess Hera, was the most renowned athletic festival in which women could compete to showcase their athletic abilities as well as gain respect and honor as an athlete – and even so, this celebration excluded the married women. Little is known about this festival other than what a 2 CE Greek traveler, Pausanias, tells us in his description of the Temple of Hera in the Sanctuary of Zeus. The festival was organized and supervised by a committee of sixteen women from the city of Ellis. Legend has it that out of gratitude to Hera for her marriage with Pelops, Hippodameia assembled sixteen women and inaugurated the Heraea.

One of the most vexing problems in dealing with the Heraea is that there is no secure date for the beginning of the festival. Pausanias intimates that cult activity already existed in the prehistoric period. Olympia may already have been the center of cult practice, perhaps as early as the Early or Middle Bronze Age with worship being devoted to divinities associated with fertility, possibly continuing into the Late Bronze Age.

Pausanias described a game at Heraea as follows: “the games consist of foot-races for maidens. These women are not all of the same age. The first to run are the youngest; after them come the next in age, and the last to run are the oldest of the maidens. To the winning maidens they give crowns of olive and a portion of the cow sacrificed to Hera.” There may also be dedications of statues with the names of the winning girls inscribed on them.

Unmarried girls had a number of advantages from married women at Olympia. Unmarried girls not only had their own athletic contests of the Hera festival in which to participate but, along with prostitutes, they were also allowed to watch the men’s and boy’s contests of the festival of Zeus – presumably to enable them to find potential husbands. Married women, on the other hand, were not allowed to participate in the athletic contests of the Hera festival, and were barred on penalty of death from the Sanctuary of Zeus on the days of the athletic competition for the men – presumably as their husbands would not be too pleased with them looking at the nude male athletes. The laws of the city of Ellis decreed that should a female participant be caught in the Olympic stadium, they were to be thrown into the river from Mount Typaion.

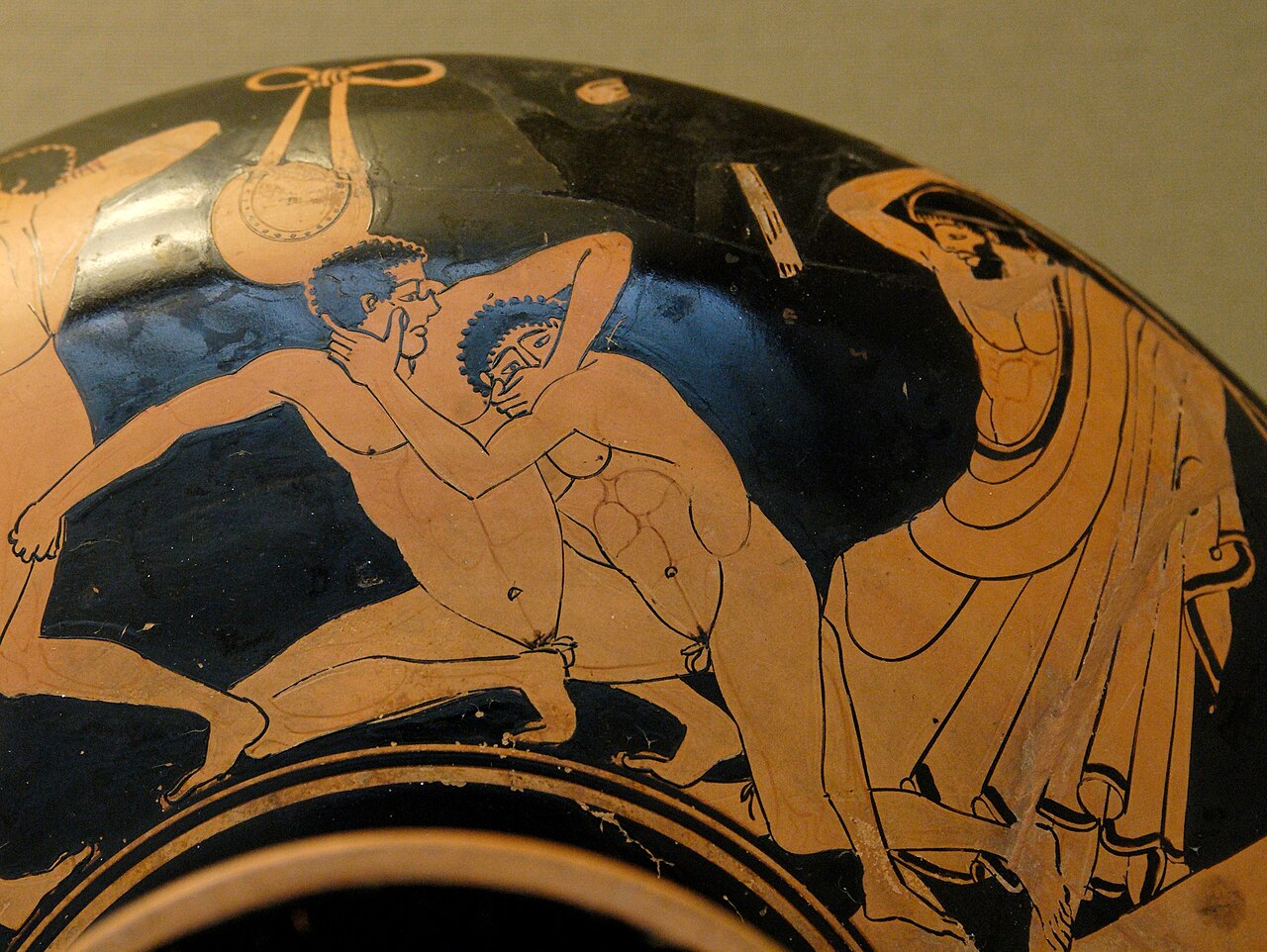

Women were subject to different rules and procedures in athletic competitions than that of men. Events for women were automatically given a handicap and the intensity of the activity was lessened. The track for the footraces, for example, was 158 meters for women and 192 meters for men. Another noticeable difference would have been the required clothing. Men were encouraged, even required, to do athletic activities in the nude while, according to Pausanias, the women wore their hair free down their back and a tunic hanging as low as the knees covering their left shoulder and breast. One theory about this difference of clothing seems to stem from societal appreciations of male beauty over female beauty of the time. To suggest that females were to do athletic events in the nude would apparently seem absurd.

This idea is exemplified by one discourse found in Plato’s Republic where, although the idea of equal education for men and women is considered to be a good idea, women are not to be treated as equal as the men in sports, as “the most ridiculous thing of all will be the sight of women naked in the palaestra, exercising with the men, especially when they are no longer young; they [the women] certainly will not be a vision of beauty.”

Although the punishments against women watching the Olympic Games were harsh and lethal, evidently this law was subject to negotiation. Kallipateira, a widow from a noble family, disguised herself as a trainer to watch her son compete and win the Olympic prize for Boxing, as she no longer had a husband to train her son. Pausanias reports that Kallipateira disguised herself as a gymnastic trainer, and brought her son, Peisirodus, to compete at Olympia. Her son was victorious and, in her fit of joy, Kallipateira jumped over the enclosure in which she was placed along with the other trainers. Her gender was quickly discovered. However, despite the threat of death for married women to attend the games, Kallipateira was unpunished out of respect for her father, her brothers, her late husband and her son, all of whom had been victorious at Olympia. But, her incident set in motion the passing of a law for the future trainers to strip before entering the arena – making this the beginning of what is to become a gender test later adopted at the European Athletics Championships at 1966.

This law may already have been an extension of the requirement for the male athletes to compete in the nude. To ensure that a male was competing, athletes were nude when they participated in the games, leaving no room for women to sneak in disguised as men and compete. However, there was one important loop-hole to this rule which allowed one woman to not only participate in the games but win twice.

Kyniska (or Cynisca) was the daughter of King Archidamus II of Sparta. Unlike Greek women, Spartan women could inherit land and belongings from their fathers or husbands. When her father died, Kyniska inherited part of his wealth and his horses. She bred these horses and entered them into the tethrippon, the horse racing event. Under a small loophole in the rules, the owner of the horses who won the event were the winners of that event instead of the racers or the horses. The racers were usually slaves and therefore not eligible to receive the honor of a winner of the Olympics.

As horse racing was costly and because Greek women generally did not have the means to breed and care for them, the issue of gender was never raised in the winner of the horse racing events. In 396 BC, Kyniska entered her horses into the races and she won. Despite everyone’s surprise at finding out the owner of the horses was a woman, nothing could be done. Kyniska became the first women to compete and win an Olympic Sport, and she tried again four years later at the next Olympics and won again.

Although she was denied entering the stadium for the ceremony and to collect her prize, as part of the reward for the winners, Kyniska was allowed to place her statute in Zeus’s sanctuary. She commissioned the inscription to read, “I declare myself the only woman in all Hellas to have won this crown.” Kyniska’s win in the “all male” Olympics set a precedence for more women to enter into the Olympics under the same loophole and win the event as she did. Some notable women include Eurylonis of Sparta who won two-horse chariot races in 369 BC and the Hellenic courtesan Bilistiche who won in 264 BC and went on to become a mistress of Ptolemy II Philadelphus.

The fact that the first female Olympic champion came from Sparta was not a coincidence. Sparta, Kyniska’s city state, also encouraged women to engage in sport in general. However, they did not seem to have the same restrictions as the rest of Greece. On top of this, Sparta also had an educational system for women—something very different than other areas of Greece, as ancient Greek women were not educated formally. Sparta women would therefore freely engage in sporting activities all throughout the city state and many areas of Sparta would hold mini contests of wrestling and running for women.

As part of a Spartan girl’s education, she would have been permitted to exercise outdoors with the Spartan boys, which was impossible in the rest of the Greek world. A proper Greek woman would not usually set foot out of doors, other than maybe to collect water from the cistern. Yet Spartan women not only exercised, they also participated in athletics competitions, competing in events like footraces.

The laws of Sparta were developed by Lycurgus, a legendary lawmaker who, in the seventh century BC reorganized the political and social structure of the polis. The law reforms of Lycurgus also included certain rules and allowances for Spartan women.

Though these rules made it seem that Spartan women were freer than the average Greek female, they were really implemented first and foremost to ensure that Spartan society progressed as disciplined, powerful, and threatening. Spartan women were considered the vehicle by which Sparta constantly advanced— a healthy and intelligent Spartan woman would produce strong and intelligent Spartan children. Therefore, the allowance of exercise and athletics for Spartan women, though looked down upon by the rest of the Greek world, was not really seen as a freedom by the Spartans. Despite the fact that Spartan women were allowed to mingle amongst the Spartan men, they were still seen as little more than baby-makers. The Spartan methods and motives were just a little different than the rest of the Greeks, and it has proven to produce stronger and more “daring” women such as Kynestra and Eurylonis.