Semar is probably one of the oldest characters in Indonesian mythology who was said to not have been derived from Hindu mythology. He was made famous by performances of Wayang (Shadow Puppets) in the islands of Java and Bali as a rather unattractive, short man with breasts, a great sized behind, and uncontrollable urge for farting. However, underneath his peculiar appearance, Semar plays a major part in the Indonesian creation myth as the elder brother of the supreme god Batara Guru (the Hindu god Shiva).

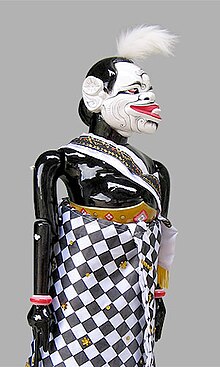

In traditional Wayang performances, Semar acts the part of a jester and a retainer for the kings. In his depictions in the performances, he does not have the elaborate ornamentation commonly found on the heroic characters, as he represents the man of the people. Semar is also known as the dhanyang (territorial spirit) of Java and a pamong (leader) of the people. He is often referred to with the honorific Kyai Lurah, which roughly translates as Honored Chief. He is therefore often called Kyai Lurah Semar.

There are many versions of the myth of Semar. A likely explanation for this is that not only that he comes from an oral tradition of storytelling, which still largely persists to this day; the stories of ancient deities in Indonesia are considerably more fluid than their Indian, Chinese or Western counterparts. This means that storytellers had no qualms about changing or adding stories or characters to suit the moral being taught or for pure artistic license. In many cases, characters from the traditional performance of Wayang (Shadow Puppets) were modified to suit the political or religious agenda at the time. It is therefore not unusual to see centuries old characters discussing the current Indonesian politics in a Wayang performance.

The origin of Semar, for example, ranges from him being the father of Shiva to the grandson of Sang Hyang Ismaya. After the spread of Islam in Indonesia, versions saying that Semar was the grandson of Adam, the first man, also circulated. As a retainer, Semar is generally recognized as the youngest Pandava brother, Sahadeva’s retainer. Yet, one would still see him as a retainer for the prince Rama from Ramayana or any of the other Pandava brothers from Mahabharata.

According to one version, of the book Purwacarita, Semar is actually Sang Hyang Ismaya, elder brother of Batara Guru, and father of Batara Surya (the Hindu sun god Surya).

He was one of the three powerful warrior gods born from a single divine egg. His brothers are Sang Hyang Antaga and Sang Hyang Manikmaya (who later took on the name Batara Guru). When it was time to decide which one of them was to be the ruler of heaven, Sang Hyang Antaga and Sang Hyang Ismaya quarreled for the position in a battle that went on for forty days. Their father, the ruler of heaven, finally decided to hold a contest. The brother who was able to swallow the heavenly mountain would be crowned as the next ruler of heaven.

As their father looked on sadly, Sang Hyang Antaga tore his lips in his attempt to swallow the mountain. He lost a lot of blood and collapsed on to the earth. Sang Hyang Ismaya choked as the mountain entered his throat and fell unconscious. When the two brothers regained their consciousness, they could no longer recognize each other. The mighty warrior figure of Sang Hyang Antaga had changed; His body now short and bloated, his mouth huge, ripped by his effort to swallow the mountain and forever marked his face. Sang Hyang Ismaya, whose face was fair like the sun, had turned into a little old man with small limbs and sad eyes. His mouth gave a perpetual clownish smile which makes him look rather frightening.

Their father banished them both to earth. Sang Hyang Antaga was renamed Togog Wijomantri and was assigned to care for the giants, whose natures were filled with rage. Sang Hyang Ismaya was renamed Semar Bagranaya. He was charged to care for the kings, Brahmins (priests and wisemen) and knights of the world, whose natures were filled with pride. Thus the two brothers bowed their heads and accepted their fates. Semar came down to earth to serve as servants to the kings and warriors.

According to Babad Tanah Jawi, Semar was a spirit who looked after a small field near Mount Merbabu ten thousand years before there were any other people in the island of Java. His descendants, the spirits of the island, came into conflict with the first people as they cleared fields and populated the island. To end this feud, a powerful Hindu priest provided Semar with a role that allowed him and his descendants to stay. The role is that of a spiritual advisor and divine supporter of the royalty. As this is a hereditary role, his descendants who are willing to protect the humans of Java also remain there.

Although he was banished to the human realm, Semar was blessed with eight divine virtues: He would never feel hungry, never feel sleepy, never fall in love, never feel sad, never feel tired, never be sick, never feel heat and never feel cold. Those eight virtues are represented by the eight hairs on his crest. Those eight chest hairs are not the only unusual quality of Semar. In fact, Semar’s very being is full of contradictions. He has a man’s face, but he has a woman’s breasts. He has wrinkles on his face like an old man, but his hair is cut like a child. His lips always smile but his eyes are sad. He is a deity, but he wears kawung motive sarong, as other retainers wear. His outward appearance is considered grotesque, but he has a kind heart.

Semar is the symbol of the duality of life, like yin and yang, where opposites exist side by side in harmony. Any attempt to change his appearance, if it was even possible, would prove disastrous. For example, a forelock is often something that children have, whereas on Semar, an old man, it shows child-like qualities such as honesty and lack of prejudice. If his forelock were cut off, he would lose these qualities and became suspicious and prejudiced like other adults. This symbolizes the importance of balance and acceptance of the good and bad qualities, as one cannot exist without the other.

Semar also has trouble controlling his tendency to fart. However, this tendency happens to be his greatest weapon. Kentut Semar (“the fart of Semar”) is every bit as feared as a hero’s bow and arrows. The fart of Semar is also very symbolic. The fart comes from within Semar, instead of a “tool” such as metal or wood like Arjuna’s bow or Bhima’s mace. Therefore, it teaches self-reliance. Semar uses his “weapon” not to kill his enemies, but to remind them of the virtuous way, because a fart cannot kill, no matter how smelly it is. With farting being considered uncouth and disgusting, Semar would only use it as a weapon as a last resort, when all other conventional ways to solve a problem have failed. The fact that the fart comes from the lower part of his body and frequently occurs when the kings and heroes are having conflicts symbolizes the need for stability in the government (the “higher ups”) so that the people below them do not suffer.

In every Wayang performance, Semar is the only character who dares to protest to the gods, including Batara Guru and Batari Durga, even compelling them to act or desist.

He often represents the realistic view of the world in contrast to the idealistic view held by the heroes. His role is somewhat similar to Shakespeare’s Falstaff in Henry IV as critic of the play’s worldview and antidote to pride.

Semar is sometimes said to be the ancestral spirit of the island of Java itself, and he is sometimes invoked in healing or protective rites. Even today, in some areas of Indonesia, carvings, puppets, and gongs are considered by some to be objects in which ancestral spirits can temporarily reside. Performances of puppetry are held once a year at cemeteries where the founders of each village are buried and ancestors are believed to have particular favorite stories. Although such ritual stories are performed infrequently today, they remain a part of the history of the art.

The origins of the Wayang performances are based on the ancient belief that shadows are the manifestations of ancestral spirits. The different forms of music, dance, and drama used in Wayang, along with similarities in their cultural and literary heritages, have created bonds of mutual appreciation among Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists in Indonesia for centuries. Wayang expresses the Javanese etiquette through its stories, which believed that an enlightened person must maintain placid stability and psychological equilibrium. Javanese ethics recommend the importance of reaching the psychological state of inner stillness, to become like a pool of clear water in which one can easily see to the bottom. The mystical and ethical ideology of the Wayang is still widely appreciated among Indonesians.

Just like Semar, there are also different versions of the beginning of Wayang. Widespread development of the art seemed to have taken place during the Hindu-Buddhist period, especially between 800 to 1500 CE. According to legends, a prince named Aji Saka brought aspects of Indian culture to Java. A long ritual opening to the wayang performance celebrates his arrival on the island. The prince came bearing the hanacaraka, the Sanskritized Javanese alphabet, thus transmitting literacy throughout the land. There may be some truth in this as the poetic language used by puppeteers in songs and narratives is laced with Sanskrit-based words and the repertoire of Wayang performances are largely based on the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the great Hindu epics. The Balinese, who remained Hindu while Islam dominates the rest of Indonesia, believe that wayang was introduced by refugees from Majapahit, the last Hindu-Buddhist kingdom on Java, before it fell in 1520.

However, some Javanese puppeteers say that the art was invented by the wali songo (the nine guardians), the nine “saints” who converted Java to Islam. One story often told by Sundanese puppeteers is that one of the saints, Sunan Gunung Jati, was having a conversation with another saint, Sunan Kalijaga, about how to present Islam to a wider public. Sunan Gunung Jati drew the outline of a Wayang figure on the ground with a stick. Sunan Kalijaga then created the first puppet and presented his first performance in the local mosque. It should be noted that by the time of the spread of Islam in Indonesia, a lot of familiar Hindu and Buddhist myths and legends, as well as folk stories, were modified to make room for this new religion. Therefore, it was very possible that history was also somewhat modified.

A group of Hindu temples, named after the characters of Mahabharata and Semar himself, were built around the ninth century on the Dieung Plateau. They are considered to be the oldest temples in Java. Historians suggest that these temples were built under commission of the kings of the Sanjaya Dynasty. A stele which was found in the area is dated on the year 808 CE. A statue of Shiva found in this area is now in the national Museum of Jakarta, Indonesia.

The temples in this complex include the temple of Arjuna, the temple of Semar, the temple of Srikandi and the temple of Gatotkacha. The temple of Semar is considered very similar in structure to the Parasuramesvara temple in India.

It stands facing the temple of Arjuna and it was used as a storage area for items needed to worship at the main temple, which in this case is the temple of Arjuna. The earliest clear depiction of Semar as a figure in Javanese arts is during the Mahapahit era (circa 1358) in relief of Sudamala in Tigamangi temple, and in Sukuh temple (circa 1439). Both reliefs were said to have been copied from a Wayang story from the period where Semar was first known to appear.

My books on Semar and other Shadow Puppet stories are available on Amazon. Click here to check them out.

![The Three Realms (Wayang: Stories of the Shadow Puppets Book 1) by [Martini Fisher]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/618qb2oidvL.jpg)